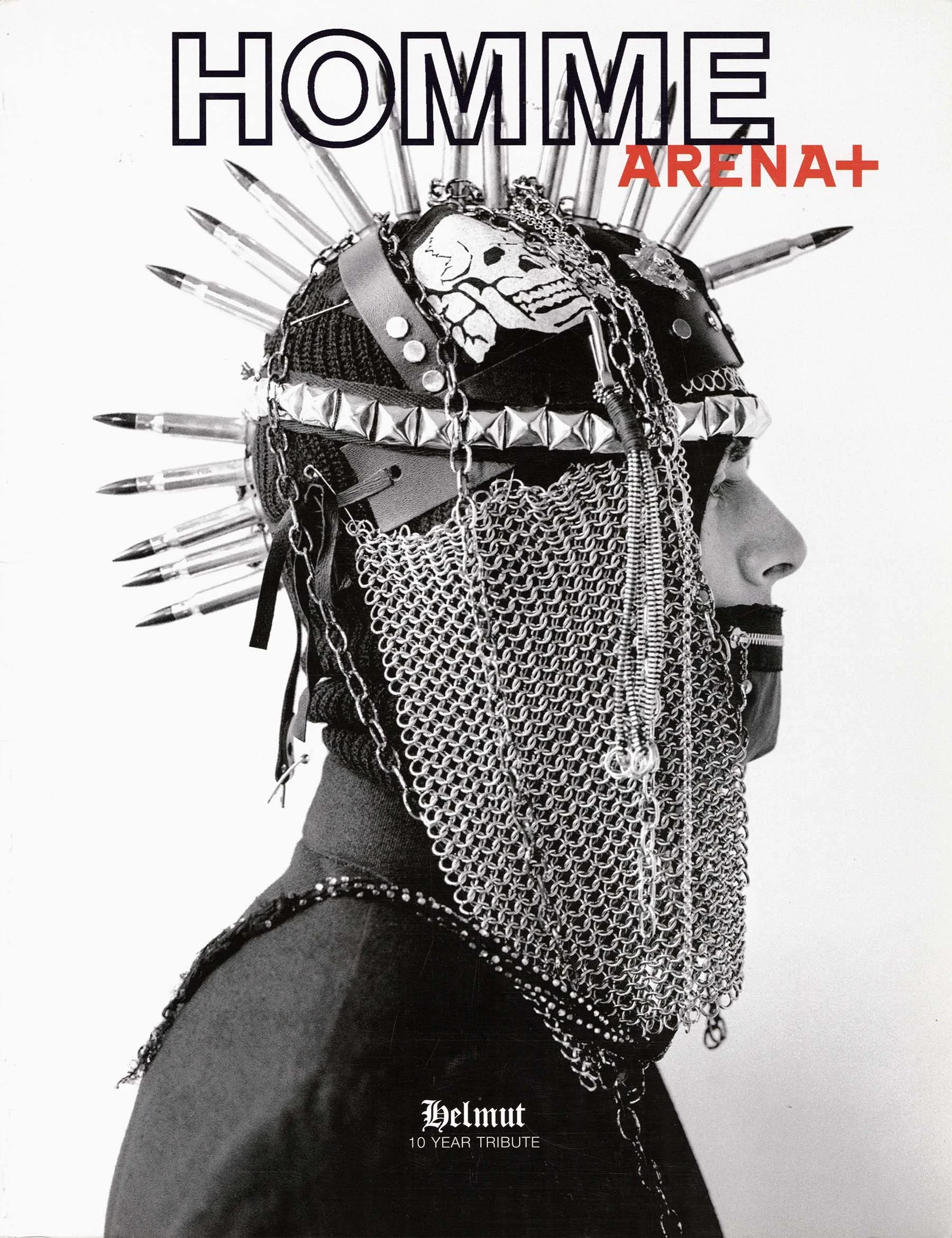

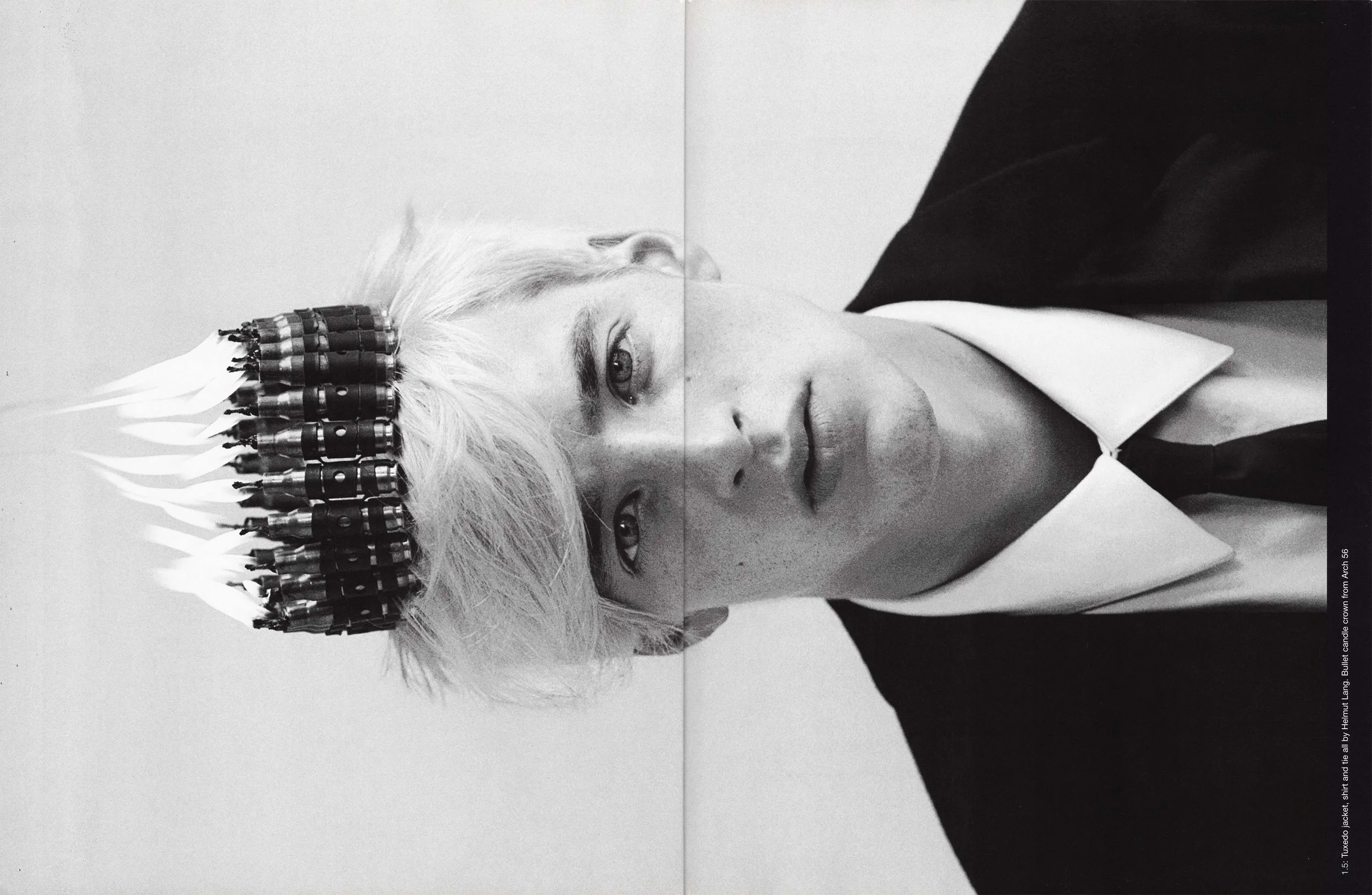

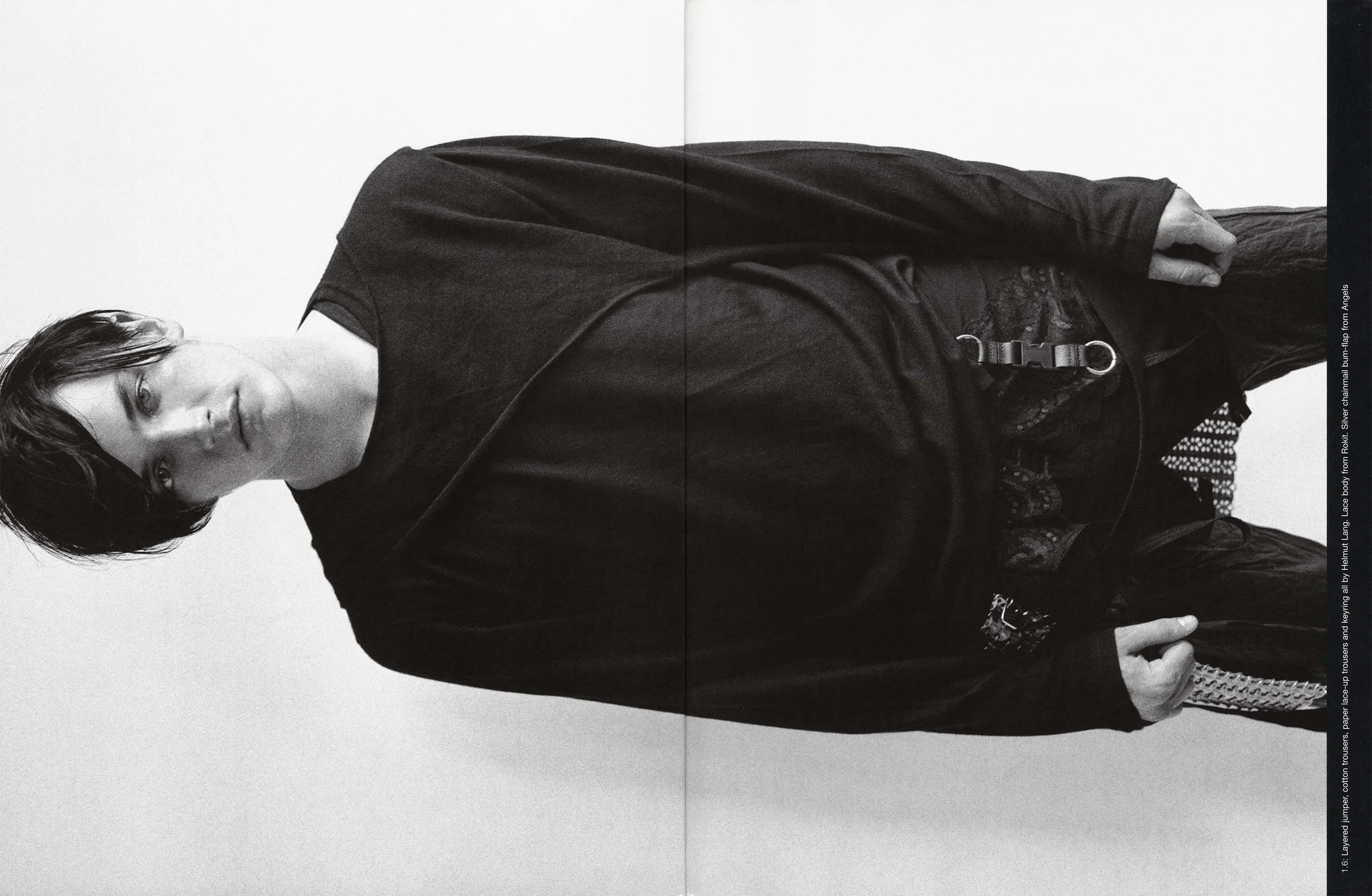

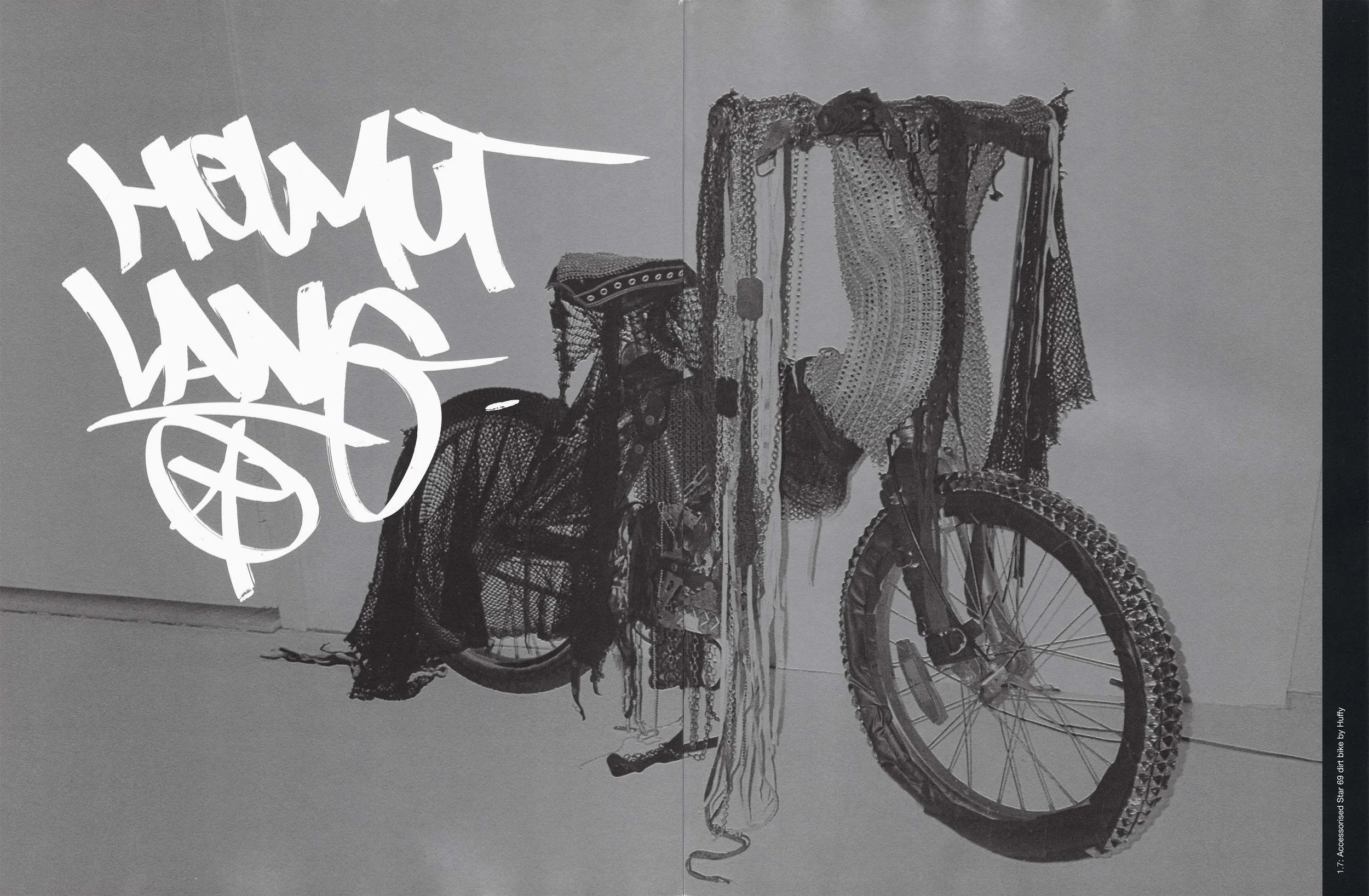

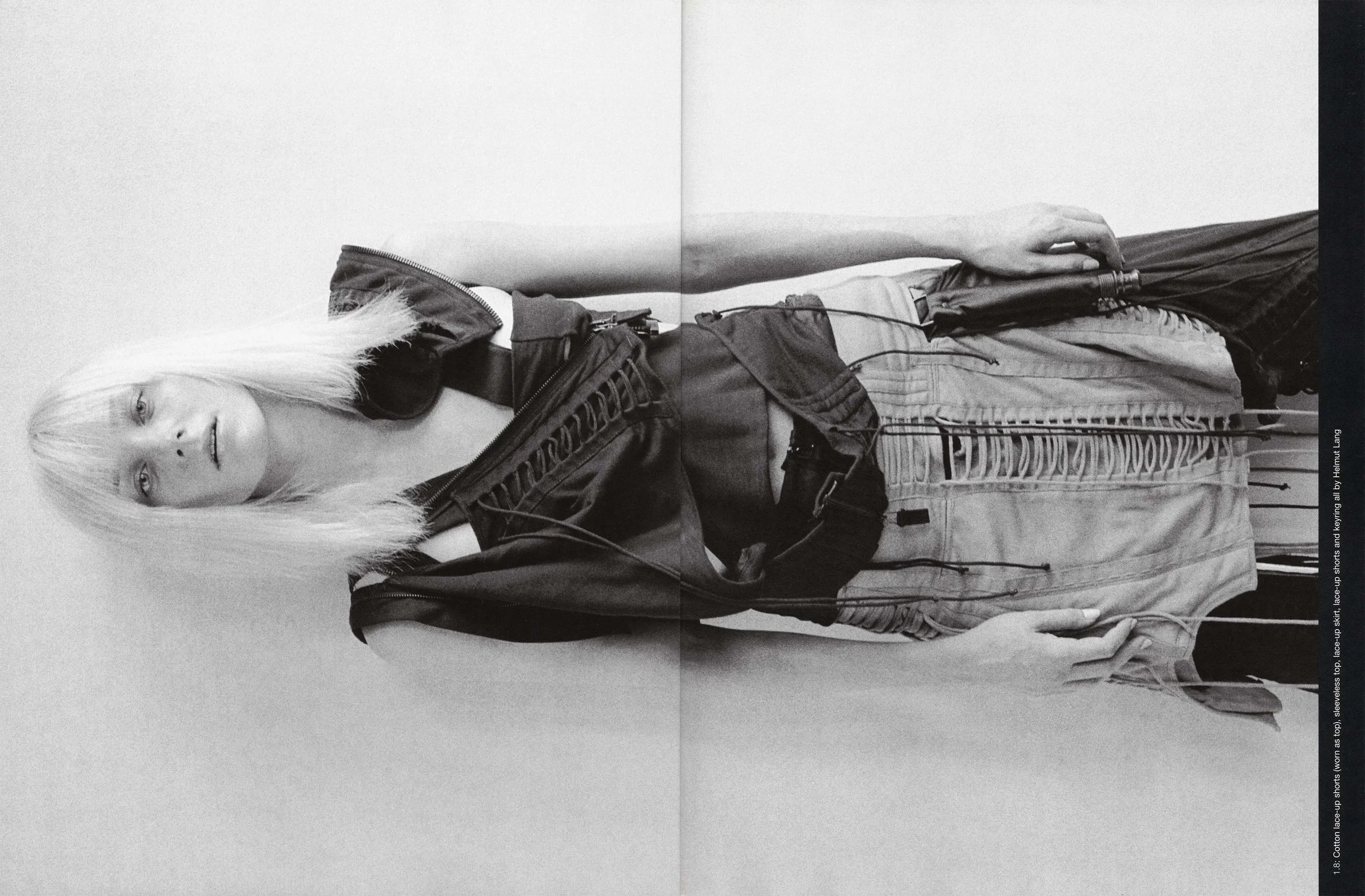

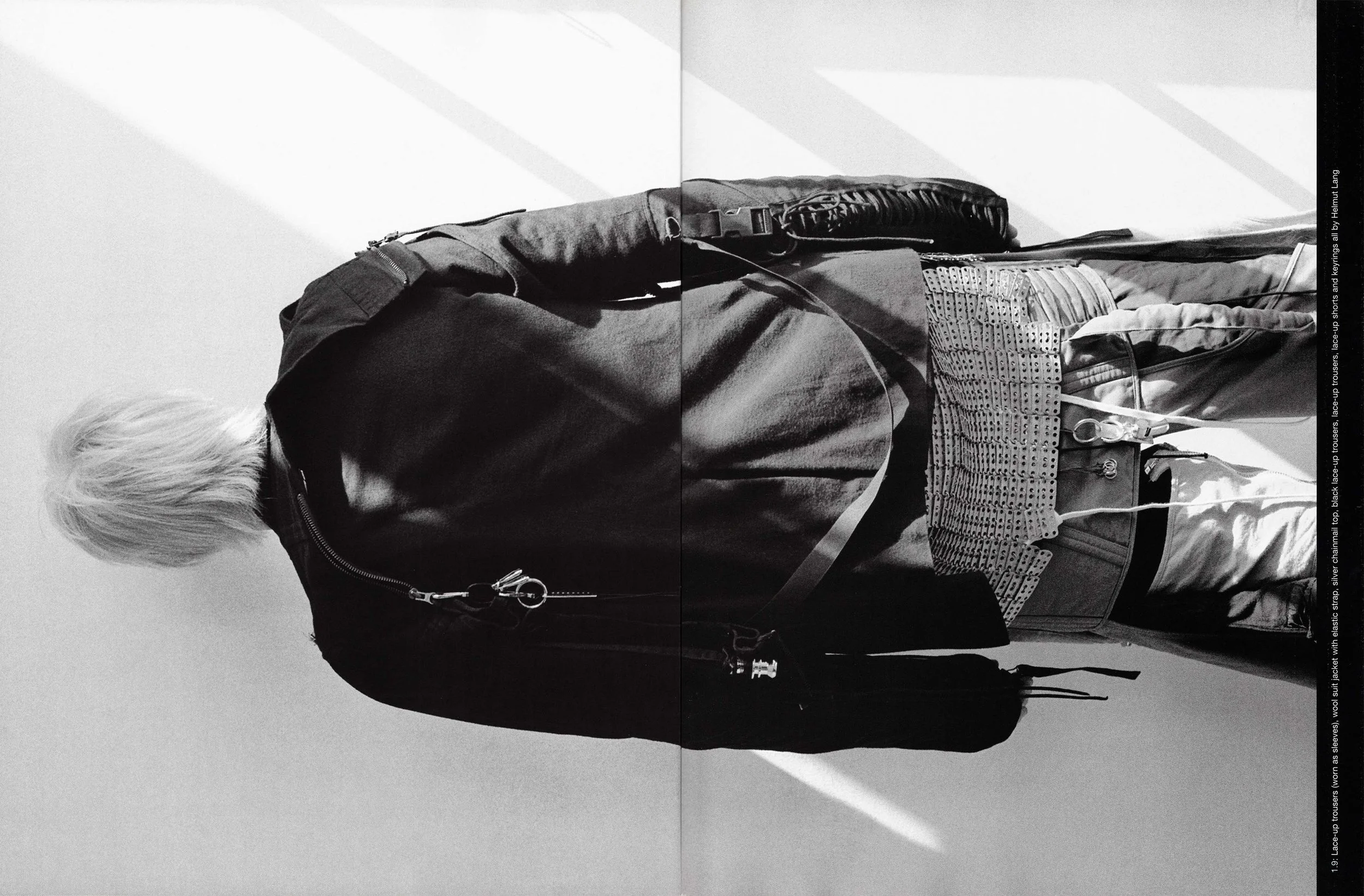

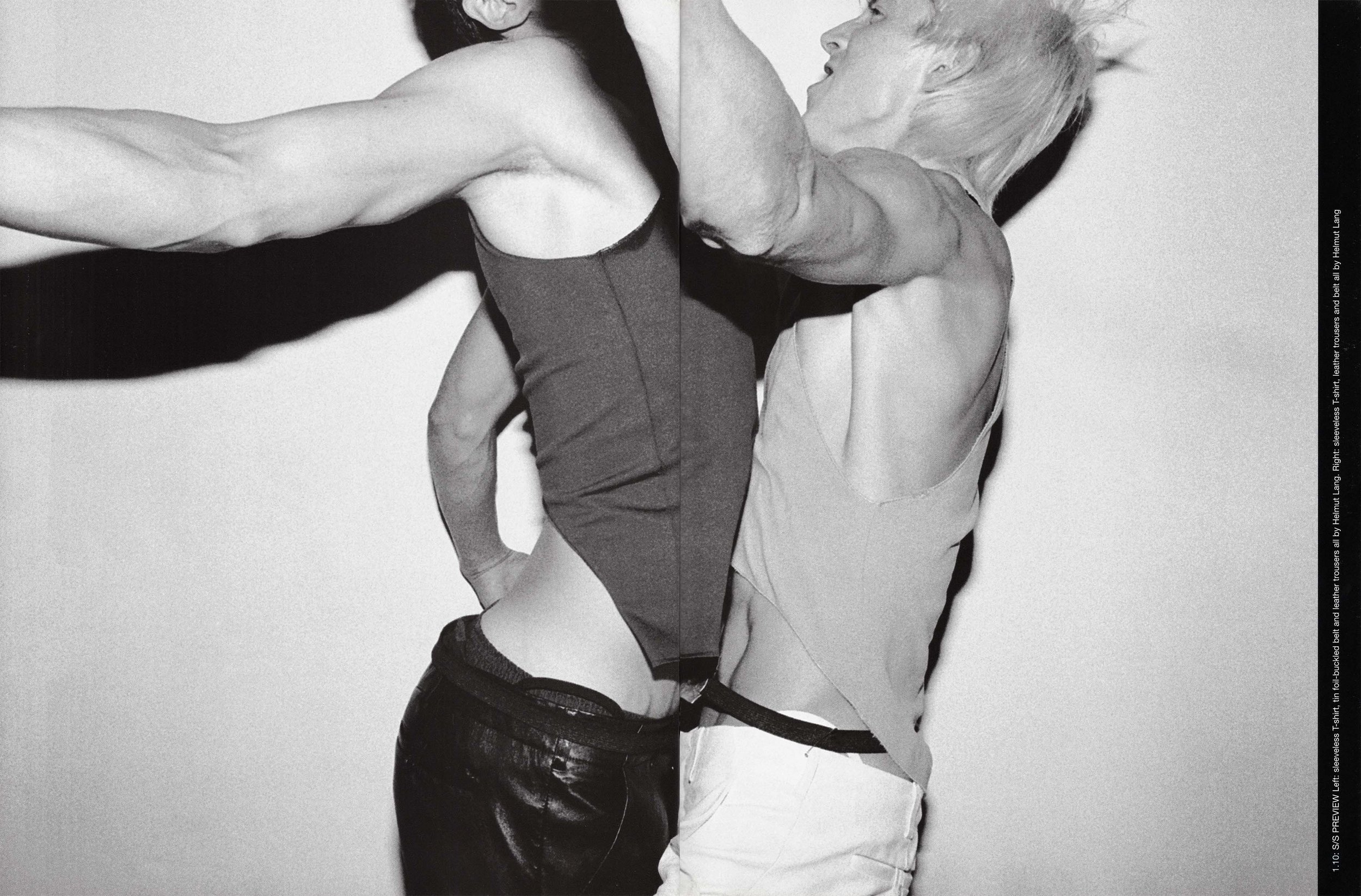

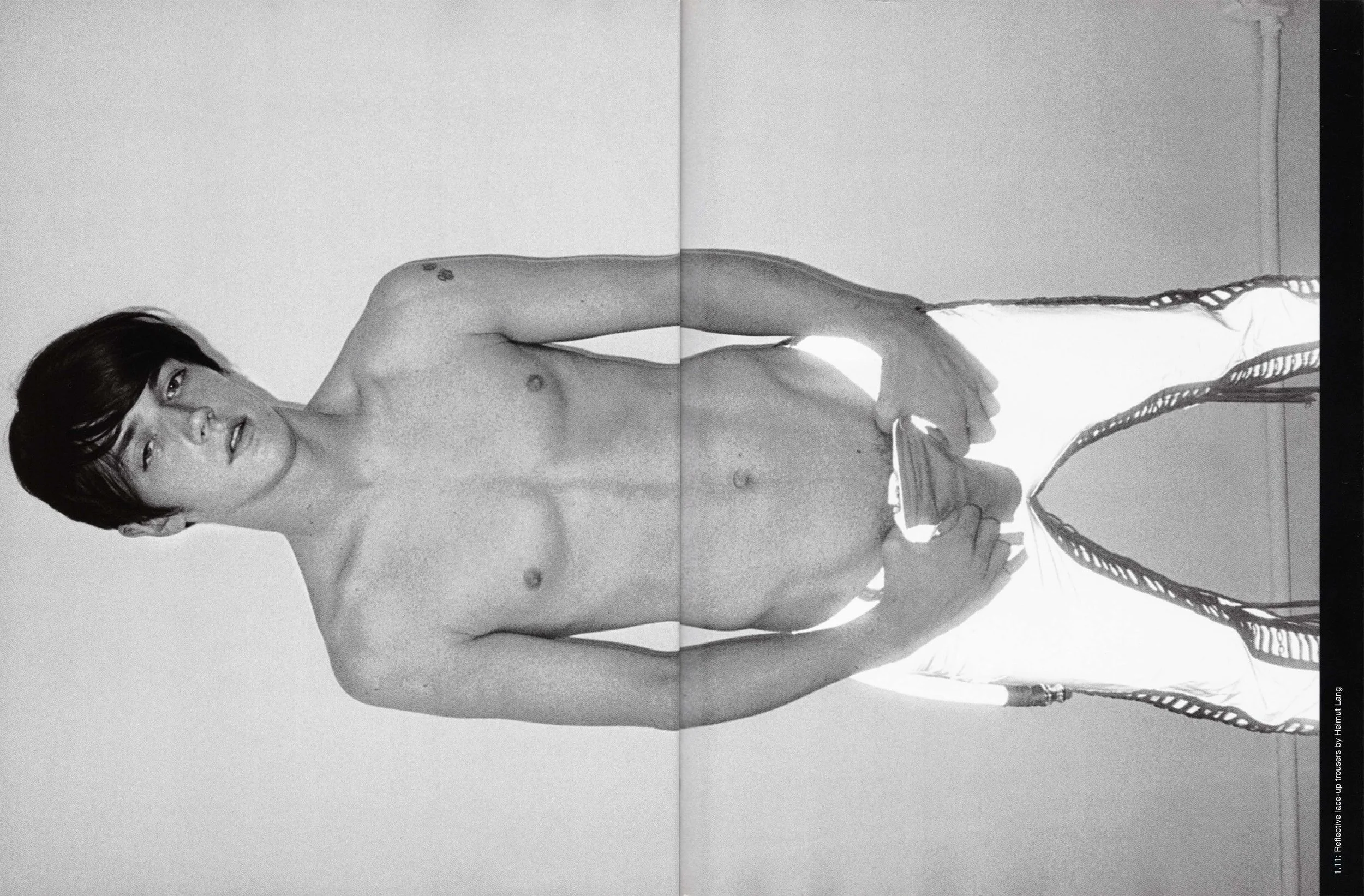

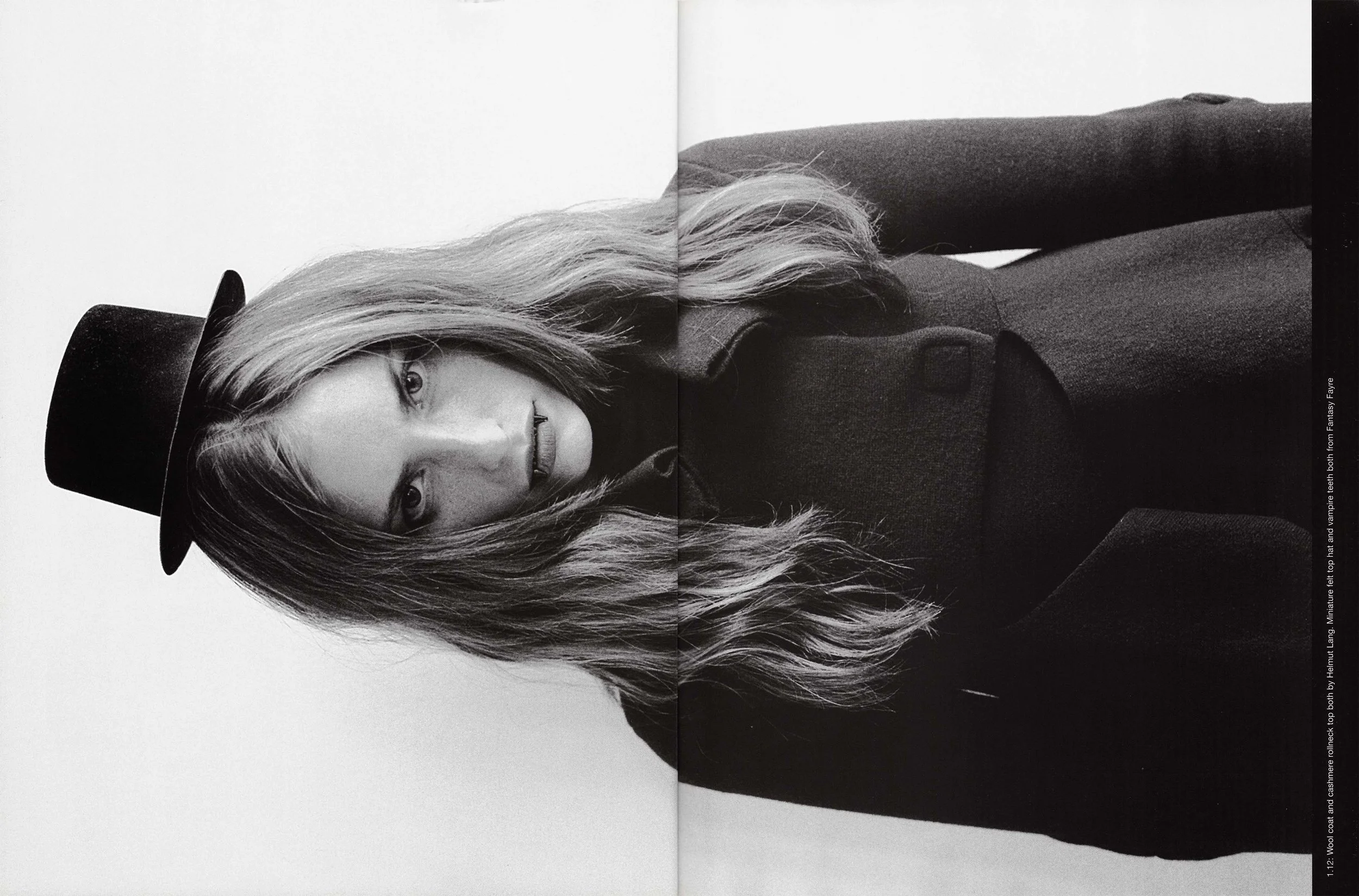

Helmut Lang

Autumn/Winter 2003-04

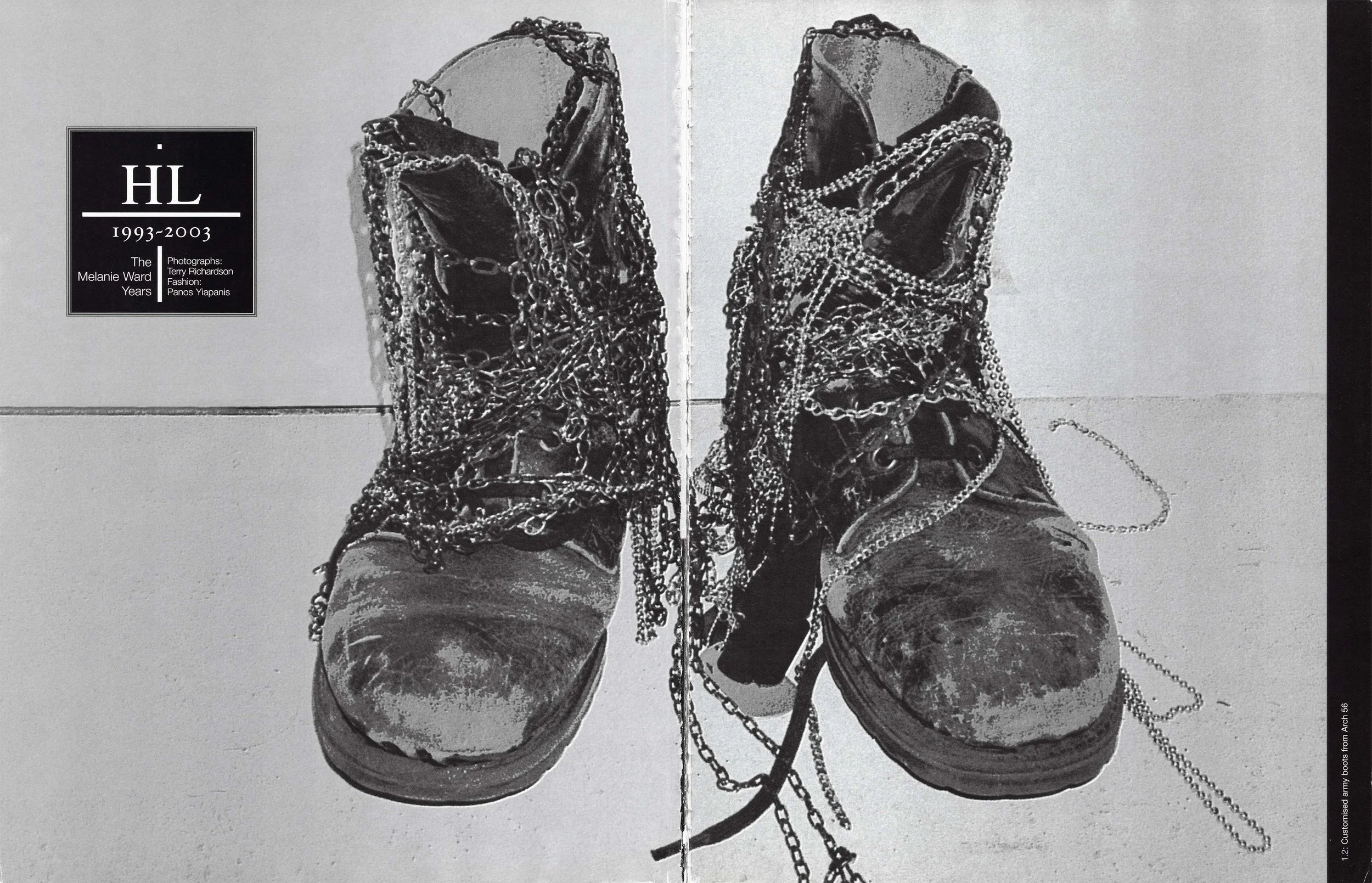

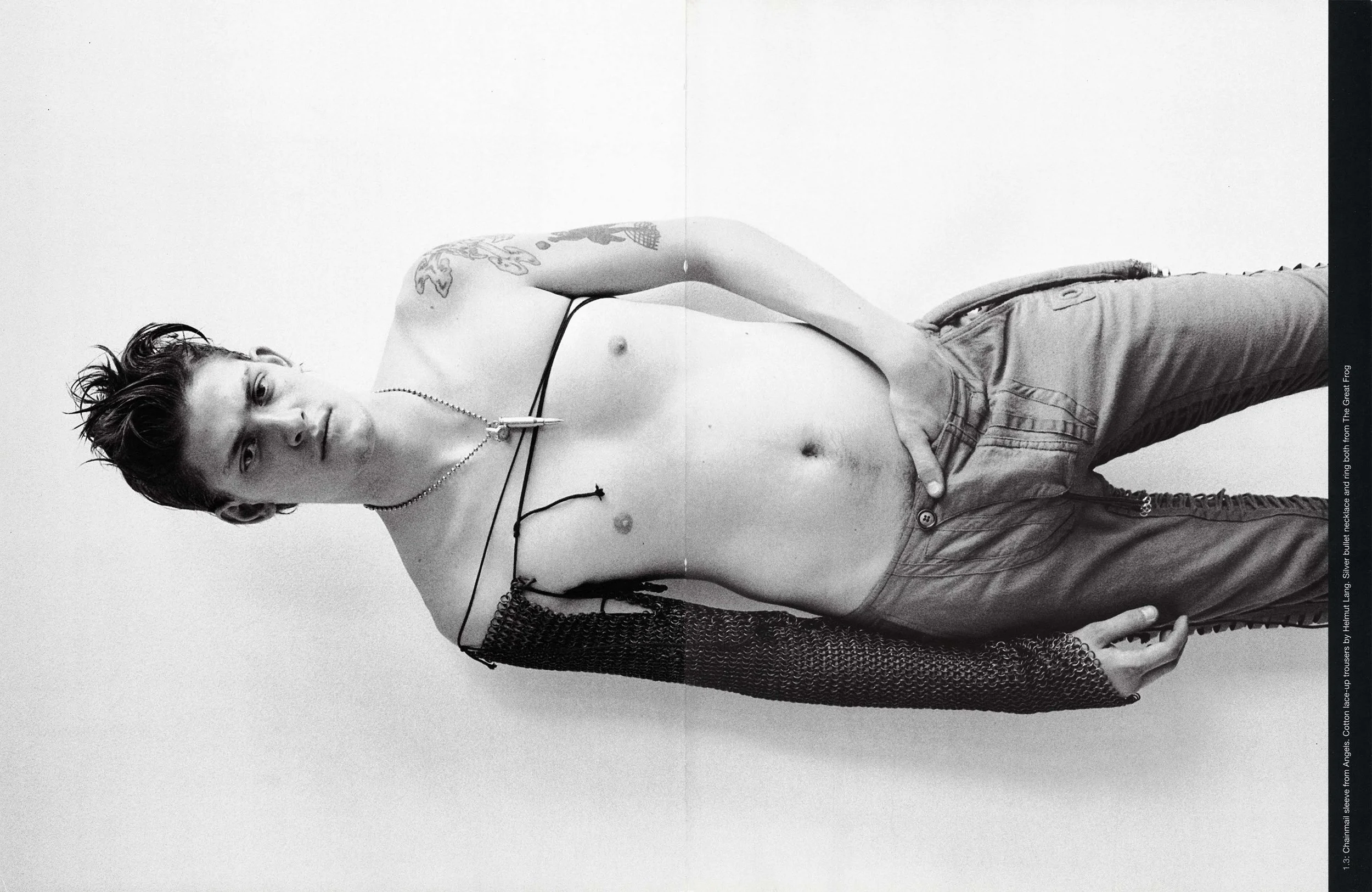

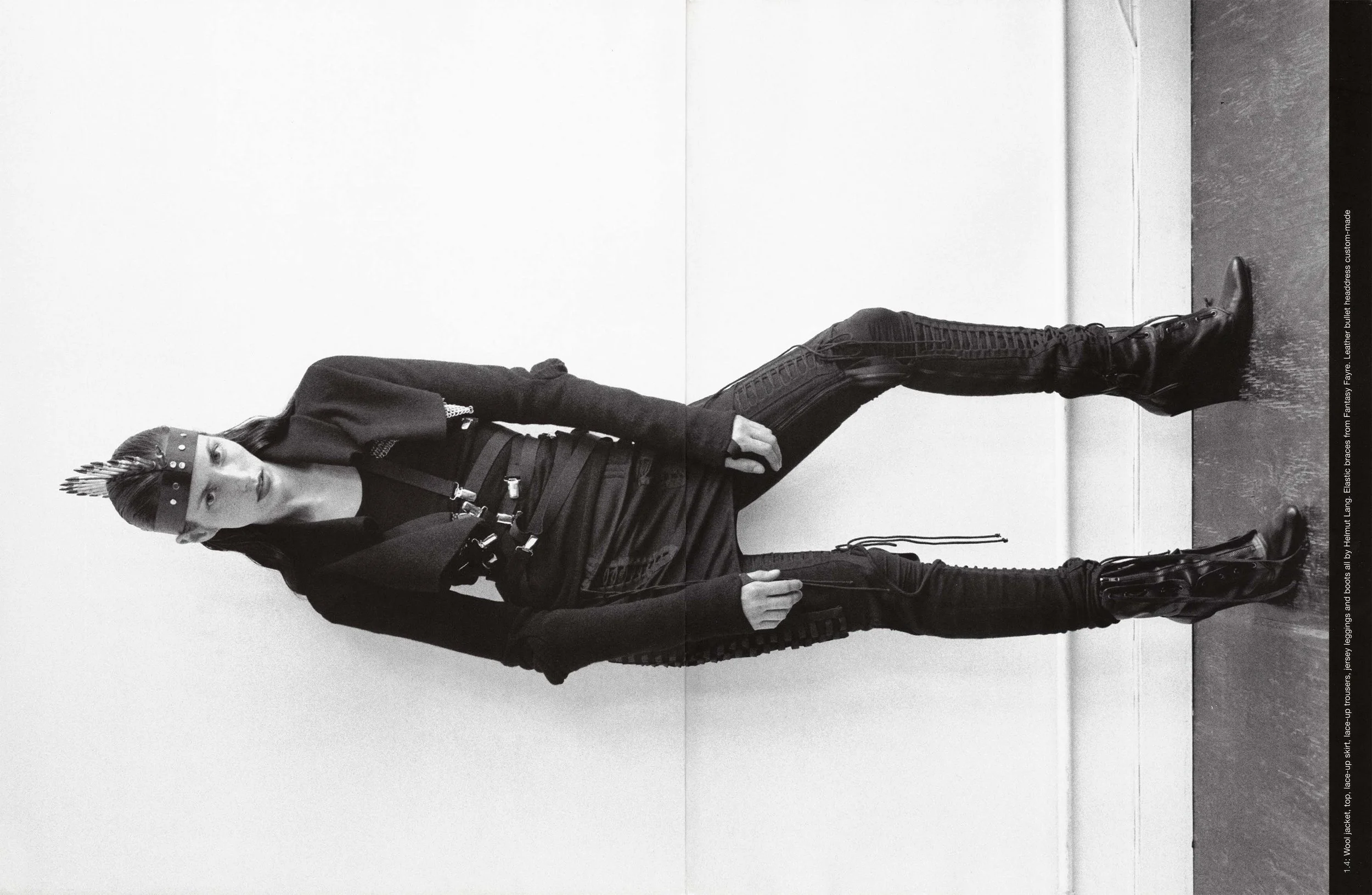

HL 1993~2003: The Melanie Ward Years

April 2003

Arena HOMME+

Photography by Terry Richardson

Styling by Panos Yiapanis

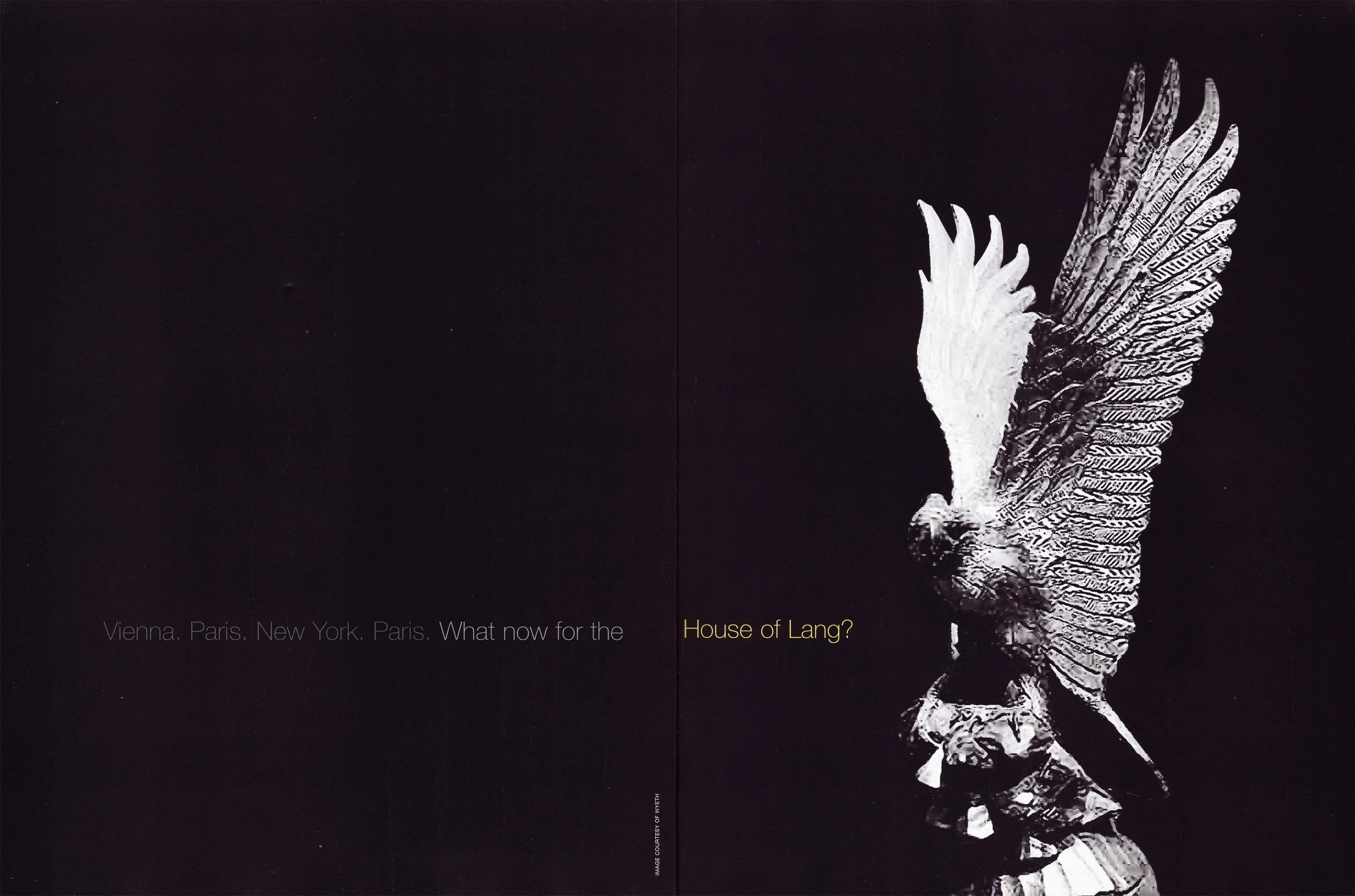

Vienna. Paris. New York. Paris. What now for the House of Lang?

April 2003

Arena HOMME+

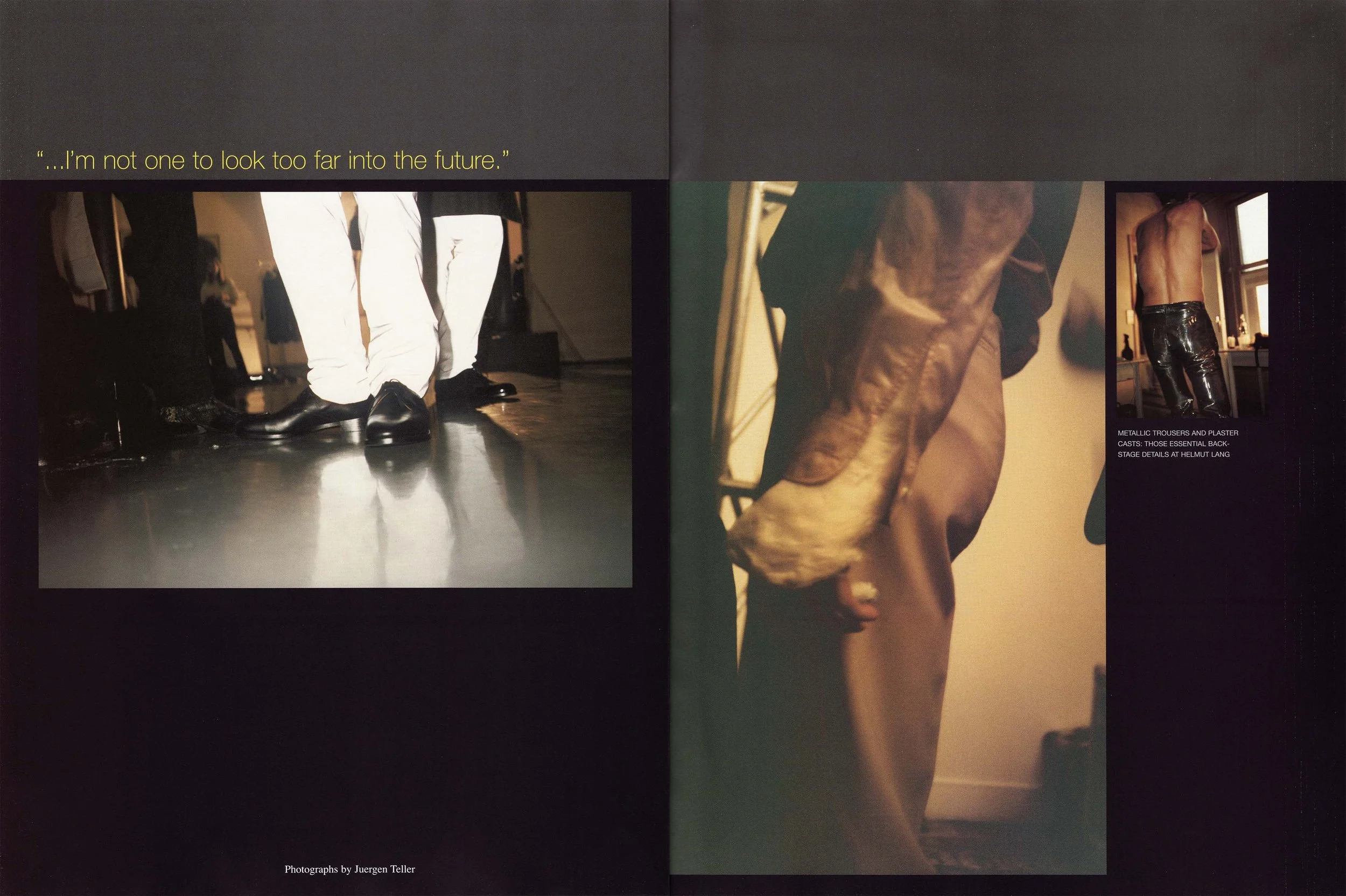

Photography by Elfie Semotan and Juergen Teller

It is the day before the day that Helmut Lang starts his summer holidays. Staff across his numerous Greene Street offices try hard not to break into a sprint while grabbing the last few minutes of his time; the huge wooden eagles that furnish the front of his SoHo store are being hoisted away for a summer, er, spring clean; and Helmut? Helmut is a model of relaxed Euro New Yorker zen. If things don't get finished, then, heh, he's tried his very best this week. Now there's a beach front home on Long Island waiting just a couple of hours' drive away. And the phone number's certainly not listed in the directory.

But first Helmut Lang will entertain Arena Homme +. A friendly, guarded chat about the past ten years of critical acclaim and a rapid growth in the glamorous world of international fashion. A world Helmut has somehow never quite fitted into smoothly, but one he's certainly been busy reshaping to requirement. As usual, Helmut sports a simple cashmere V-neck and jeans today. As usual, people are in the store round the corner buying much of the same. Everything in it's right place.

Interview Ashley Heath

ah: First up, congratulations on the amazing reception this autumn/winter collection is getting, Helmut. It really is a definitive moment for Helmut Lang and the praise you've been getting is well-deserved, especially as it's a daring collection. Where did the inspiration for something this provocative come from?

HL: I guess the times we are in are somewhat unstable, and with the way it has been economically I find it inspiring to just go ahead and do something exciting. The whole economic situation is not what it was at the end of the Nineties, so for me it's the perfect time to be very creative and experimental and push things forward. When the financial establishment is not having such a good time, it's a good time for creativity.

ah: Your conviction right now is that you need to be doing something experimental, extreme even, to persuade people to walk into the stores and spend their money?

HL: Well, I have to say that's not really my main motivation. But I want to get a message straight across, as powerful a message as possible. The whole fashion marketing thing, I don't think we ever really got there anyway.

ah: Yet you have your name plastered over all those New York cabs...

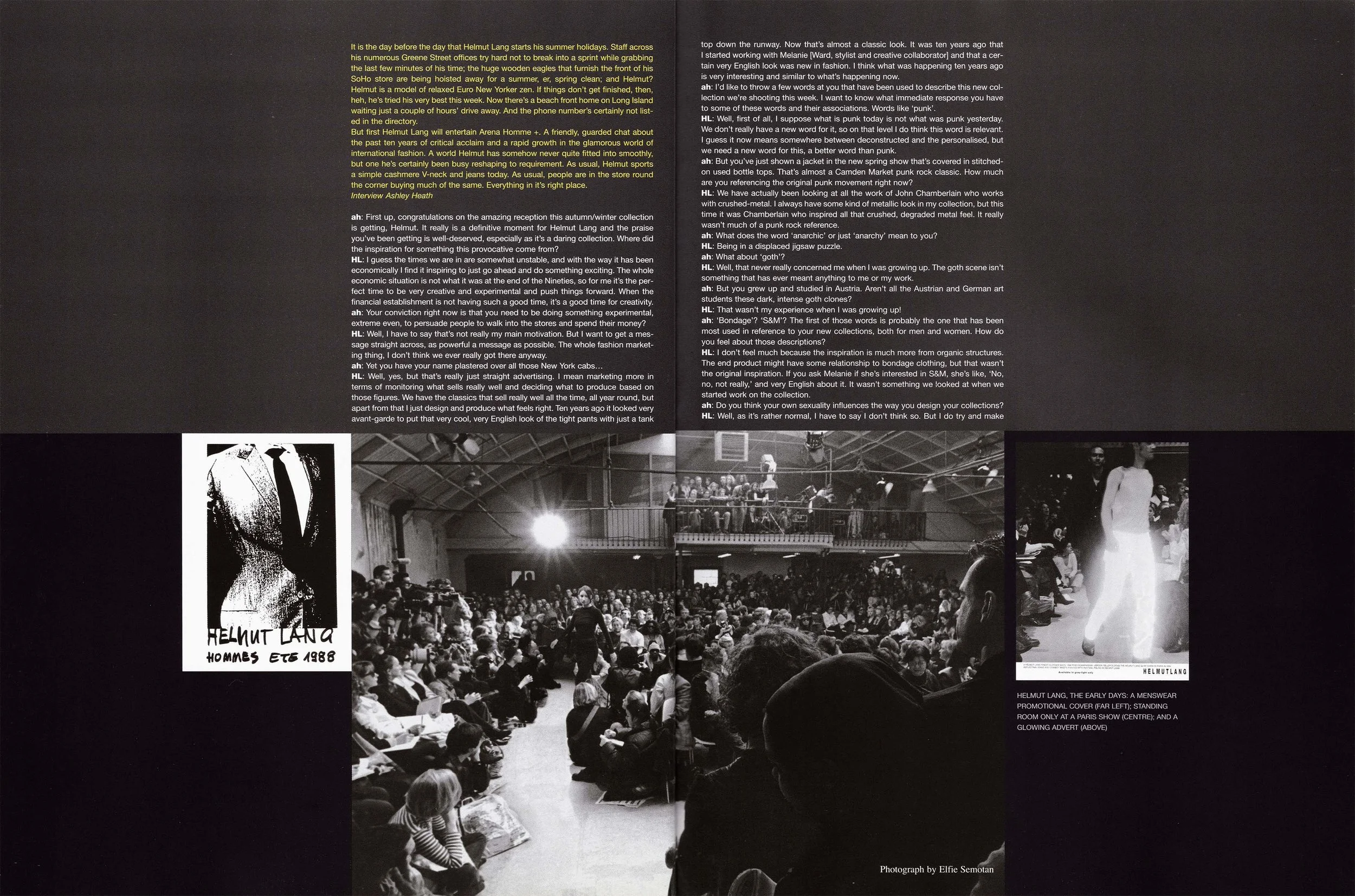

HL: Well, yes, but that's really just straight advertising. I mean marketing more in terms of monitoring what sells really well and deciding what to produce based on those figures. We have the classics that sell really well all the time, all year round, but apart from that I just design and produce what feels right. Ten years ago it looked very avant-garde to put that very cool, very English look of the tight pants with just a tank top down the runway. Now that's almost a classic look. It was ten years ago that I started working with Melanie [Ward, stylist and creative collaborator] and that a certain very English look was new in fashion. I think what was happening ten years ago is very interesting and similar to what's happening now.

ah: I'd like to throw a few words at you that have been used to describe this new collection we're shooting this week. I want to know what immediate response you have to some of these words and their associations. Words like 'punk'.

HL: Well, first of all, I suppose what is punk today is not what was punk yesterday. We don't really have a new word for it, so on that level I do think this word is relevant. I guess it now means somewhere between deconstructed and the personalised, but we need a new word for this, a better word than punk.

ah: But you've just shown a jacket in the new spring show that's covered in stitched-on used bottle tops. That's almost a Camden Market punk rock classic. How much are you referencing the original punk movement right now?

HL: We have actually been looking at all the work of John Chamberlain who works with crushed-metal. I always have some kind of metallic look in my collection, but this time it was Chamberlain who inspired all that crushed, degraded metal feel. It really wasn't much of a punk rock reference.

ah: What does the word 'anarchic' or just 'anarchy' mean to you?

HL: Being in a displaced jigsaw puzzle.

ah: What about 'goth'?

HL: Well, that never really concerned me when I was growing up. The goth scene isn't something that has ever meant anything to me or my work.

ah: But you grew up and studied in Austria. Aren't all the Austrian and German art students these dark, intense goth clones?

HL: That wasn't my experience when I was growing up!

ah: 'Bondage'? 'S&M'? The first of those words is probably the one that has been most used in reference to your new collections, both for men and women. How do you feel about those descriptions?

HL: I don't feel much because the inspiration is much more from organic structures. The end product might have some relationship to bondage clothing, but that wasn't the original inspiration. If you ask Melanie if she's interested in S&M, she's like, 'No, no, not really,' and very English about it. It wasn't something we looked at when we started work on the collection.

ah: Do you think your own sexuality influences the way you design your collections?

HL: Well, as it's rather normal, I have to say I don't think so. But I do try and make men always look masculine and sexy and then make women look very feminine and sexy. I think when I design it's more in terms of taking care of the body than in trying to specifically inject sexiness. That can look very crude and obvious and I think a lot of other collections are too concerned with that. For me it's all about thinking about the body and how to design for it, treating men's and women's bodies differently, and achieving a kind of cool factor that hopefully leads to a feeling of sexiness

ah: You talk of 'taking care of the body'. In your own life how health-conscious are you in terms of looking after yourself, your diet, your exercise…?

HL: Not enough. I think every normal man now is a bit concerned with these things, but certainly in Europe people still like to smoke and to drink.

ah: And you still feel your outlook is very European?

HL: I still think like a European. New York feels very right for me, it feels very modern and au courant. It's the most urban environment I know and yet New York has actually lightened me up. I came from middle Europe, where they love to be a little melancholic and concerned with head things.

ah: They still take free jazz seriously...

HL: They don't have the black humour of, say, the English that helps balance things and lighten things up. I think that's why New York has been good for me in terms of lightening me up. That said, there are still things about American culture that seem slightly strange to me, like the way Americans tend to automatically smile madly as soon as a camera is pointed at them. That's really strange. You come to New York and it already seems familiar to you because of movies and TV and so on, but then suddenly these little things show you how culturally things are different here. Fundamentally, the view here is 'you can do and be whatever you want'. The European view tends to be more 'you should be happy for just being alive'. I think a combination of European and American outlooks can be really good. My close friends in New York tend to be an even split of American and European, although no one was actually originally from New York. We all came here.

ah: Tell me who your three closest friends here in New York are.

HL: No!

ah: You're a Pisces, aren't you? Tell me what that means.

HL: Good question... hmm, well they're supposed to be emotional, sensitive, creative and introverted. Pisces question everything — I do think that's me, and it's useful for my work. But with the whole astrology thing, I don't want to ever pursue it too far, because if you think that everything's laid out for you then I don't know what your life would really mean day-to-day. I have had my chart done, though. My rising house is Gemini, the good and the evil twin, so things are never boring!

ah: Do you find yourself pulled in two directions? The whole creative versus business conflict must become an issue...

HL: Well, I'm not so sure I'm such a good businessman — I'm really am very emotionally led.

ah: There aren't many fashion designers who have huge company offices on New York's Greene Street. You've got to be pretty good at the business stuff...

HL: It's all an optical illusion. This is a place of work so it has to look a certain way. But on the business thing, I would say I am very focused. Actually, let me take that back, I'm not focused at all. But once I have got stuck into a project I am very focused to see it through and to follow it up.

ah: Do you want to have a huge impact on the industry?

HL: If you ask me that now I would have to say yes, because otherwise it's pointless. You put all that work and energy behind it all, so hopefully it will have an impact.

ah: Would you say you have a big ego?

HL: It depends... When you get a certain reputation, I guess it makes you competitive to keep that reputation or live up to expectations. But I also have this middle-European thing of never wanting to push myself forward in a vulgar way.

ah: And how do you feel when you now see the yellow cabs driving by with your name on the top? It's not like it's just any old brand name — it's your name. It would feel strange for me to walk round New York City and see my name on the top of every other taxi.

HL: I'm very good at ignoring it. I don't think anything when I see that name now — it's more the company than me. I block it out. I just try and lead as normal life as possible. I certainly try and stay out of the limelight, you know that. I'm very aware that there's a borderline with celebrity, and once you go across it there's no way back.

ah: Have you ever had any kind of therapy or counselling?

HL: No, never. I'm not against it, but I guess I talk with my close friends about everything. I'm from that coffee-house culture, where you sit there all day drinking coffee and just talk about everything.

ah: You lost your parents when you were still young. Tell me about how that affected your upbringing.

HL: Well, my grandparents raised me anyway and I didn't have that much contact with my parents. My mother died when I was a teenager. But my grandparents obviously had a profound effect on me and I was raised up in the mountains. It was a strange environment for someone my age, in a way. And then in my early twenties I thought that I should be running around trying to catch up on what I missed. But quickly I realised that actually I was very gifted, that being raised by my grandparents was definitely a blessing in disguise.

ah: What do you think when you read that a peer like Tom Ford says he would now like to have children? Any thoughts in that direction?

HL: I have never allowed myself to comment on other designers. But let me answer you in another way. If I was to live my own life again, I would live it in exactly the same way. I'd change nothing. I don't think I've missed out on anything.

ah: Are you checking out any of the über-dark music coming out of the drum and bass scene? I know you've always been passionate about electronic music.

HL: No, I haven't. I don't think there's been any really exciting music scene as such since 1996. But I've only been in a record store about three times since moving to New York, so I don't really know everything any more. I just think there's no incredible newness now. At the beginning of the Nineties the electronic music scene was so fresh and new. That was the time that really excited me.

ah: I was wondering how big an influence Ralf Hutter and Kraftwerk had been on you? The keeping yourself behind the scenes and letting the brand identity do the hard work. Almost constructing a corporate public face, a facade of sorts.

HL: Kraftwerk were not actually that big an influence for me. Surprising, maybe. The keeping-myself-behind-the-scenes was more to do with what I said before... I was happy to do a lot of things but I wasn't eager to just do everything. I never wanted to be one of these people who go to the opening of an envelope.

ah: Who were the big influences and inspirations on you?

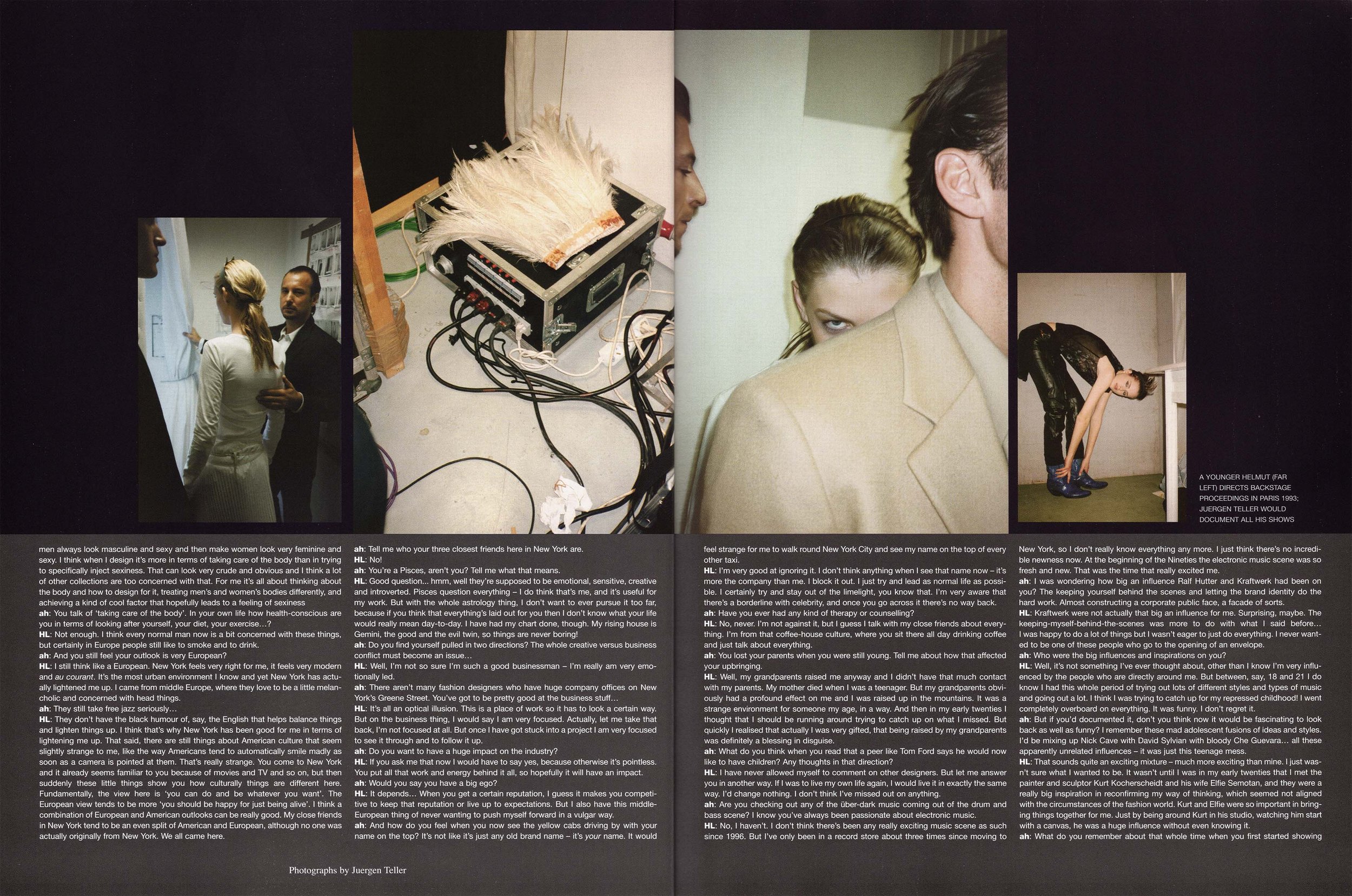

HL: Well, it's not something I've ever thought about, other than I know I'm very influenced by the people who are directly around me. But between, say, 18 and 21 I do know I had this whole period of trying out lots of different styles and types of music and going out a lot. I think I was trying to catch up for my repressed childhood! I went completely overboard on everything. It was funny. I don't regret it.

ah: But if you'd documented it, don't you think now it would be fascinating to look back as well as funny? I remember these mad adolescent fusions of ideas and styles. I'd be mixing up Nick Cave with David Sylvian with bloody Che Guevara... all these apparently unrelated influences — it was just this teenage mess.

HL: That sounds quite an exciting mixture — much more exciting than mine. I just wasn't sure what I wanted to be. It wasn't until I was in my early twenties that I met the painter and sculptor Kurt Kocherscheidt and his wife Elfie Semotan, and they were a really big inspiration in reconfirming my way of thinking, which seemed not aligned with the circumstances of the fashion world. Kurt and Elfie were so important in bringing things together for me. Just by being around Kurt in his studio, watching him start with a canvas, he was a huge influence without even knowing it.

ah: What do you remember about that whole time when you first started showing in Paris?

HL: I remember Melanie's work in The Face, i-D and Arena particularly — the pictures of Kate Moss with Corinne Day and the pictures of that guy Ashley that David Sims took too. So I wrote a letter to Melanie telling her I loved her work and would she be interested in working with me. I just looked at these pictures in the magazine and felt something special, that there was something similar here to the way I was thinking. We met up at the Café Flore and that was the start of where we are now. The first show I did with Melanie was the one with Stella in it in ’93, but it must have been two or three years before that that I first started seeing her work.

ah: That work has stood the test of time, and it's to your credit that you recognised its vitality and how important it was. Most of the fashion establishment would choose to criticise or just plain reject this alternative point of view. I think they saw it as in opposition to their business, rather than an exciting challenge. Ironically, your business flourished as a direct result of your courage. As soon as you began working with Melanie, did you think your collections went to a whole different level?

HL: I think the work got much more reassured. There was a definite chemistry and it was the exchange of communication that enabled some really interesting things to come out from that point. It was a magic combination because we would think just the same about a lot of things.

ah: But she didn't work exclusively for you back then?

HL: No, Melanie worked for all sorts of people: for Prada, for Calvin Klein. As soon as we could afford to sign her exclusively to us, though, we did that. And she was happy with that. She always had the same kind of energy for the work I had. She still has no official title here, but then neither do I.

ah: I wanted to ask you about those golden years showing in Paris when you first teamed up with Melanie and every show was celebrated, every blue cowboy boot and every luminous trouser became a fashion industry cause célèbre...

HL: Well, for me the high point was the two seasons of 1994, the spring/summer and autumn/winter, which were the second and third collections Melanie and I worked on as a team. With the first of those two, we had a problem with production and we needed another shape; we couldn't get any more fabric, so we had to improvise. It was the first collection that had the Scotch tape sewed onto the clothes, and it worked out so well. But it was all from necessity really. I really regret giving away so many of the samples from that time, because I have nothing left.

ah: You'll make me feel guilty, because you used to give me clothes. You were always very generous.

HL: Maybe I can buy everything back off you now?

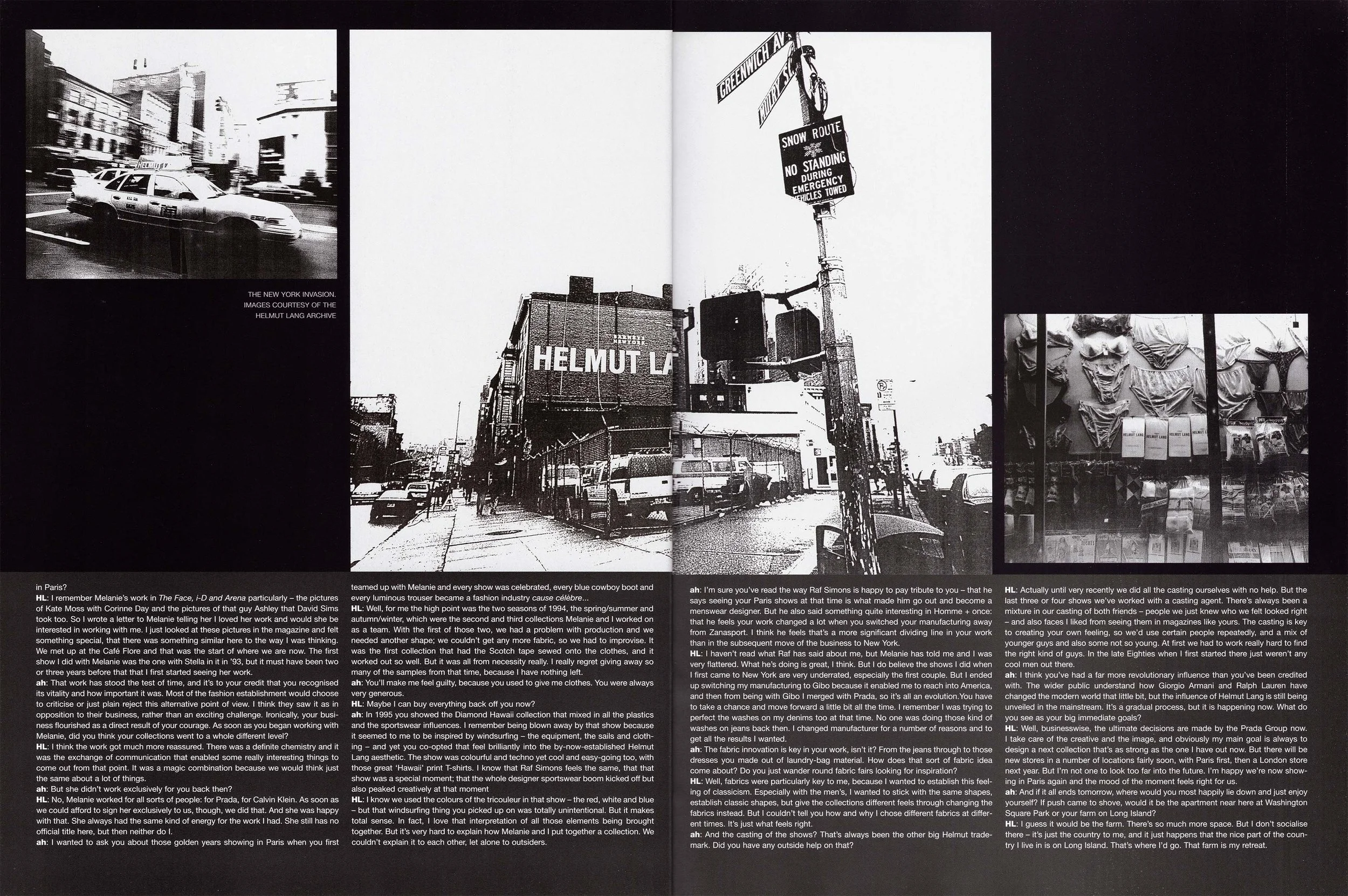

ah: In 1995 you showed the Diamond Hawaii collection that mixed in all the plastics and the sportswear influences. I remember being blown away by that show because it seemed to me to be inspired by windsurfing — the equipment, the sails and clothing and yet you co-opted that feel brilliantly into the by-now-established Helmut Lang aesthetic. The show was colourful and techno yet cool and easy-going too, with those great 'Hawaii' print T-shirts. I know that Raf Simons feels the same, that that show was a special moment; that the whole designer sportswear boom kicked off but also peaked creatively at that moment.

HL: I know we used the colours of the tricouleur in that show — the red, white and blue — but that windsurfing thing you picked up on was totally unintentional. But it makes total sense. In fact, I love that interpretation of all those elements being brought together. But it's very hard to explain how Melanie and I put together a collection. We couldn't explain it to each other, let alone to outsiders.

ah: I'm sure you've read the way Raf Simons is happy to pay tribute to you — that he says seeing your Paris shows at that time is what made him go out and become a menswear designer. But he also said something quite interesting in Homme + once: that he feels your work changed a lot when you switched your manufacturing away from Zanasport. I think he feels that's a more significant dividing line in your work than in the subsequent move of the business to New York.

HL: I haven't read what Raf has said about me, but Melanie has told me and I was very flattered. What he's doing is great, I think. But I do believe the shows I did when I first came to New York are very underrated, especially the first couple. But I ended up switching my manufacturing to Gibo because it enabled me to reach into America, and then from being with Gibo I merged with Prada, so it's all an evolution. You have to take a chance and move forward a little bit all the time. I remember I was trying to perfect the washes on my denims too at that time. No one was doing those kind of washes on jeans back then. I changed manufacturer for a number of reasons and to get all the results I wanted.

ah: The fabric innovation is key in your work, isn't it? From the jeans through to those dresses you made out of laundry-bag material. How does that sort of fabric idea come about? Do you just wander round fabric fairs looking for inspiration?

HL: Well, fabrics were particularly key to me, because I wanted to establish this feeling of classicism. Especially with the men's, I wanted to stick with the same shapes, establish classic shapes, but give the collections different feels through changing the fabrics instead. But I couldn't tell you how and why I chose different fabrics at different times. It's just what feels right.

ah: And the casting of the shows? That's always been the other big Helmut trademark. Did you have any outside help on that?

HL: Actually until very recently we did all the casting ourselves with no help. But the last three or four shows we've worked with a casting agent. There's always been a mixture in our casting of both friends — people we just knew who we felt looked right — and also faces I liked from seeing them in magazines like yours. The casting is key to creating your own feeling, so we'd use certain people repeatedly, and a mix of younger guys and also some not so young. At first we had to work really hard to find the right kind of guys. In the late Eighties when I first started there just weren't any cool men out there.

ah: I think you've had a far more revolutionary influence than you've been credited with. The wider public understand how Giorgio Armani and Ralph Lauren have changed the modern world that little bit, but the influence of Helmut Lang is still being unveiled in the mainstream. It's a gradual process, but it is happening now. What do you see as your big immediate goals?

HL: Well, businesswise, the ultimate decisions are made by the Prada Group now. I take care of the creative and the image, and obviously my main goal is always to design a next collection that's as strong as the one I have out now. But there will be new stores in a number of locations fairly soon, with Paris first, then a London store next year. But I'm not one to look too far into the future. I'm happy we're now showing in Paris again and the mood of the moment feels right for us.

ah: And if it all ends tomorrow, where would you most happily lie down and just enjoy yourself? If push came to shove, would it be the apartment near here at Washington Square Park or your farm on Long Island?

HL: I guess it would be the farm. There's so much more space. But I don't socialise there — it's just the country to me, and it just happens that the nice part of the country I live in is on Long Island. That's where I'd go. That farm is my retreat.