Yohji Yamamoto & Takeshi Kitano

山本耀司VS北野武:「ワル」たちの午後

Yohji Yamamoto VS. Takeshi Kitano: “Bad Boys” Afternoon

June 1997

Esquire Vol.11 No.6

Written by Shigeo Goto

Photography by Yoshiaki Tsutsui

スタジオのホリゾントの上に立った男2人よく撮られようとか、自己演出なんて、まるで意識なし。男には迫力が必要。世の男どもが弱体化してるのに、この2人の濃味ったらありゃしない。ニタニタ微笑みながら、すきあらば、いつでもグサリと刺しにかかる。やさしさ、狂気、妄執、絶望がまじった矛盾体。でも、それがこのうえなく魅力的に見えるのだから、相当な「ワル」に違いない。真昼の放談、彼らが喋り出したら、もう誰にも止められない。

Two men standing on the studio’s horizon stage—no concern at all for being photographed well or for self-presentation. Not even a hint of self-consciousness. Men need intensity. While men around the world seem to be getting weaker, these two are overflowing with raw power. Grinning slyly, they look like they’d stab you in an instant if given the chance. A contradiction of kindness, madness, obsession, and despair all mixed together. And yet, they appear irresistibly charismatic—so they must be some serious “bad boys.” Once they start talking during a midday chat, no one can stop them.

やまもと・ようじ/1943年生まれ、53歳。6年振りのソロアルバム『HEM~たかが永遠~』を発表。5月からはムーンライダースをバックに全国5都市でツアーを開催する。

きたの・たけし/1947年生まれ、50歳。カンヌで絶賛された『キッズ・リターン』に続く次作品の構想を練りながら〝殿〟としても忙しい毎日を送る。

Yohji Yamamoto / Born in 1943, age 53. Releasing his first solo album in six years, “HEM: Only Eternity.” Starting in May, he will tour five major cities across Japan backed by the Moonriders.

Takeshi Kitano / Born in 1947, age 50. While working on his next project following the Cannes-acclaimed Kids Return, he continues his busy days as the esteemed "Tono" (lord/master).

あなたたちも〝オヤジ狩り〟の対象になると思いますか?

山本 オヤジって言われても、まずオヤジってイメージがないからね。自分のことを考えても、自分では大人のつもりでいるし、まわりは気難しそうな人だとか言うんだけど、俺のことをよく知ってる人はガキ扱い。大人として扱ってくれないね。だから、不良少年が、大人になるかと思ったら年とっても不良のガキのままで(笑)。

北野 俺んちのオヤジは、名前も書けなくて、暴れてばっかしだった。家に帰ってきても、危ないのが戻ってきたっていうかねえ。話したことないし、飯なんて一緒に食ったのは1回もないんじゃないかな。

山本 オヤジは最初から、存在してなかったんですよ。自分がまだ1歳半の頃、戦争に連れてかれて、そのままいなくなったから、オヤジっていうのはいない。イメージもともとないんですよ。だから、母親と2人だけの生活。あの頃は、戦争未亡人っていうのが多かったな。

北野 テレビで『パパ大好き』とか見た時、とっても気に入らなくってね。なんだこりやと思った。でもね、うちのオヤジなんて、普段は俺やおふくろとかぶん殴るのに、江の鳥行った時に、俺が外国人にハーシーズかなんかのチョコレート1個もらっただけなのに、電車んとこで正座して「ありがとうございました」とか謝ってんの見た時、あらぁ、アメリカは強えんだなあって(笑)。

山本 うちも、家庭だとか、家族だとか、そういう雰囲気は全く知らなかったなあ。

北野 戦後すぐのオヤジたちっていうのは、戦争行って人殺ししたことがあったりするわけでしょ。そんなやつを襲ったりなんて絶対思わないんだよね。それに、俺たちの子供の頃は、近所にヤクザがいて、俺たちは、ヤクザには絶対逆らわないし、それにそいつらが、みんなオヤジなんだよ(笑)。今の若い連中にとってみれば、オヤジ連中に対する「凶暴さ」とか「怖さ」の幻想なんてないね。で、しょうがないから出したって、「全共闘」ぐらいしか出せない。「俺たちは角材で殴り合った」とかね。オヤジロ体、体からいえば17や18歳の連中とまともに殴り合ったら負けちゃうと思うけど、幻想というか裏付けがなくなっちゃったんだね。当然オヤジ狩りが始まっちゃうよね。

山本 ガキの頃に、ヘビ殺したり、動物殺したり、そういう思い出ないだろうし。弱ってる奴っていうか、人間を狩ろうってことになるんだろうね。

北野 若い奴相手にしないし、口も聞きたくないよね。要するに大っ嫌いなんだよ、本当は(笑)。若い奴は未来あるとか、のせる人がいいるけど、俺は大嫌いだな。未来は若さなんて一切関係ない。お前らなんかに、未来あるわけねえじゃねえか(笑)。個人の資質なんだから。「ガキ狩り」とか逆に出てきたりして。誰も出ないか(笑)。テレクラに電話して、呼び出されたふりして相手が集まってきたら、その外側からまたオヤジで囲んじゃう。理想的だと思うな。

山本 30代の頃、〝銀行〟が「怖い」とか思ったことあるけど、若い連中に脅威とか感じたこと全くないです。あんまり喧嘩なんてやんないですけど、今って渋谷の連中とか、ナイフ持ってる奴多いでしょ。殴ってくんのは、ちっとも怖くないけど、ナイフ出したらいけないよってこと、あいつらに体で教えなきゃだめなんだけどな。

北野 何か子供に、「常識」とか言っても、全然威力ないからね。「そんなことやってちやいけないよ」って言うよりも、ぶん殴るぞって言った方が早いし。暴力っていうのは、体と感覚が同時にガッとくるものだから。俺が育った近所って、日常的にすごい喧嘩をいっつもやってたから、殴ったり、殴られたりって当たり前だと思って育った。で、高校ぐらいまでは上野以外行ったことなかったんだけど、大学になって、池袋の地下街行ったらはじめてほかの学校の奴に脅かされて、あがっちゃって。もう、池袋とか渋谷の街歩いてる高校生なんて、とんでもなく喧嘩が強いって思ってて、もう「街」で圧倒されてるから、ついビビッちゃって。そのうち慣れてきて、何だあいつらっ、て復讐してやるかと思ったら、もういなかったりして(笑)。

山本 (笑)。僕は育ったのが歌舞伎町のド真ん中だったから、やっぱりヤバイ人ばっかりなんですよ。子供の頃、キャッチボールしてて、ボールがそれて黒塗りの車にボーンって当たると、「このガキ」ってぶん殴られちゃう。だから、ガキ殴る奴って大嫌いだった。でもGIの連中ってすごいんです。道端で、木刀で素振りの練習してた時、うしろにいたGIにもろに当たっちゃった。でも、顔真っ赤になっても怒んないんです。子供のやったことだからって。僕もたけしさんと同じように、まわりの日常が、商売の女の人とか、ヤクザものばっかりだから、逆に全然すごいと思わないし、憧れないんですよ。新宿なんて全然怖くなかったけど、池袋は怖かったなあ。

団塊世代ということばでくくられたりすることの不快感とか違和感とかありませんか?

北野 俺は、団塊の世代という一つの言い方でまとめて言われることが多いんだけど、実は、数が多いだけ、いろんな種類のやつがいて、可能性がいっぱいあった。うちの中学なんて、16クラスもあったり、そのうえ1クラス60人(笑)。1学年1000人。だから、「ワル」は本当に「ワル」なの。番長みたいなのは、今なんか本当にヤクザの親分やってるし。頭いい奴は東大出て、マサチューセッツ行って大学教授やったりと、もうすごく差がある。ところが、ずっと真ん中で適当な連中がいて、これが今言われる「団塊の世代」っていう「主流」になったんだと思う。

山本 やっぱり、たけしさんもさっき言ったけど、人ってその人一人の問題であって、世代の問題じゃないと思うな。世代とかで区切って見るっていう感覚がないし、そういう見方もあんまり好きでもないしね。外国人もよく、「ジェネレイション」とか「何年代の文化は」とかよく言うけど、その感覚がわかんない。

北野 あとで昭和の芸能を振り返った時に、俺とエノケンが同じように語られたりして、やだ(笑)。団塊とか言っちゃうと、個人が出てこないよね。この間、笑ったのは、よく最近、戦後日本人はすごく長生きしたとか言うでしょ。だけど、今80歳ぐらいの人は大正に生まれたんであって 、戦後に生まれたやつなんて、まだ50歳なんだよね。それを戦後長生きしたなんて。世代とか時代でなんかくくるとヘンなんだよね(笑)。

今の時代に対する不快感はありますか?「俺は時代と関係なく生きてるんだ」ってこともあるかもしれませんが。

山本 最近はどうもヤキがまわってね(笑)。時間っていうのは自分が生まれてから死ぬまでの間のことでしょ。人生の瞬間っていうのは、たかだか50年とか60年ぐらいだとすると、自分の時間を共有した人たちっていうのと、「一緒にやったんだな」っていうある「愛着」みたいなのがわいてきて、「あ、俺もヤキがまわってる」と思うことはあるね。

北野 俺はよく考えてみると、団塊の世代の真ん中にいるんだよね。真ん中にいて、それが嫌でしょうがなかったんだと思う。つまり、上にも下にもなれないわけだから。だから、俺の喧嘩相手っていうか、イライラの対象は、団塊の世代に対してだったのかもしれない。ずーっと世代的な意識なんてしなくても、無意識のうちに喧嘩してたんだろうな。マスコミとか「団塊の世代」とか書くでしょ。そうすると、俺だって昔からその世代の中にいるんだけど、はっきり活字で出てくると、「こいつら、俺とは全然生活違うな」、「こいつらが団塊の世代だったのか」って今になって思い知らされるね。

山本 不快より前に、まず「雄は全部、敵」みたいなところが、僕の場合あったし。母親一人でしょ、だから、太宰ほどじゃないけど、時代とか世代じゃなくて、女の人を通して世間を見てたから。幼稚園なんか、まわりは頭に白癬やおできがいっぱいできたガキがいて、僕は坊っちゃん刈りで、母親におしゃれさせられたりして、独りぼっちだったのがベースだから。まわりは敵であって、それ以上のものじゃなかったなあ。溝はあいたままでね。

北野 耀司さんもそうだと思うけど、お客さん切って、完全に孤立するわけにはいかない。でも、こっちには入れないよっていうような、柵みたいなもん完全にあるしなあ。対象にする人がなければ食えないわけだから。切る勇気ないなあって思うと、割り切れなくて、イライラしてくるよね。

山本 最近、腹立つのはね、中学生とか高校生が、「耀司さん、握手してください」とか「あの子が耀司さんのファンなんで、サインしてあげてください」とか言われるとね。そんなの、勘違い、錯覚じゃない。もうつながんないはずなのに、握手してくださいとかね。もうちょっと別のことやってるからね、っていうのは本音としてはありますから(笑)。

北野 仕事やっててギリギリしてる時に、演芸場なんかに出たら、客の中にもお前には笑われたくないって奴が必ずいる(笑)。お前は笑うなって(笑)。漫才師は笑ってもらうのが商売だから、みんなにウケりゃいいじゃねえかと思うんだけど、何かそういうのが慣れてくるとイライラしてきちゃってね。ヤクザのオヤジに、「ヤクザが笑うな」って言って裏口から逃げたり(笑)。耀司さんの世界もそうだけど、商売をやりたいのか、ただその世界に入りたいのかってことがあるよね。デザイナーって言われることが目的でその世界に入ってくる人もいるし、芸人さんとかタレントなんていう言葉が好きでくる奴もいるし。

山本 いっぱいいるんです。僕がやり出した頃から、原宿の交差点あたりに石投げりゃ、デザイナーの卵にぶつかるってくらいにね。

北野 あれ、やっぱり目的はデザイナーって言われることだけなんだね。まあ、若い奴は必ずそれから始まるんだけど。

山本 寄ってくる人たちがね、デザイナーっていうイメージに憧れて寄ってくるのか、それとも僕個人のことを本当に好きで寄ってくるのかわからない時がいっぱいあって、そういう時に「無茶」をやりたくなるんですよね。だから、生きてる目的が、無茶をいかにやるかってことですからね。別に、世界的なデザイナーになってやろうとかっていう、そんなのは、ちょっとカンのいい奴だったら、どんなにこの業界がつまんない世界かわかってるからやんない。やっぱり、カッコイイ女と一緒に暮らして、ドキドキしてた方が絶対いいし(笑)。デザイナーって、なんて言うか、「神秘の城」を築く仕事でしょ(笑)。だけど、とにかく出来上がらないようにしようっていうか、できるだけ格好悪いことしておこうっていう。

北野 自分がね、多重人格とまではいかないけど、何か二重人格かなって思うことがあって、俺自身が、「ビートたけし」っていうのを創って、そいつの友達になってるような気がしてしょうがない。独りで酒飲みながら、自分で「馬鹿だよなあ。おめえは」とか言ってる。自分を操り人形みたいにして楽しんでるとこがあって、それが、完全に一体化しちゃうと、にっちもさっちもいかなくなる。調子悪い時は、俺じゃない。うまく人形が動き出したら、またその中に入り込んじゃったりして、都合よくね。

世の中には官僚みたいなずるい奴もいます。もちろんそんな連中とは違いますが、「ずるさ」「悪さ」をもっていませんか?

北野 でも、俺は自分が2ついるような気がするから、単に自分の中の一人がものつくって、みんなにいいって言われてもうれしさが半分なんだよね。かたっぽに何かやらせて見てる時に味わう快感というのは、一人で全部やった時の半分ぐらいの感動しかないね。

山本 昔、人からよく言われましたよね。とくにファッション関係のジャーナリストからね。「耀司さん、何事かひとつに夢中になりなさいよ」って。なれないですよ。やっぱり。どっかでしらけてるから。生まれて初めてパリでショウをやろうって決めた時に、パリでやるんだから日本の着物とか絶対に出さない。逆にヨーロッパの手法でやってやろうと思いました。ほかのデザイナーは必ずストレートに日本的な要素を持ってくるわけだから。僕は、明治の前に長崎にやってきた頃のポルトガル人の格好をテーマにしてやったりした。何か、照れちゃってできないことがいっぱいある。それはシャイとか言うんじゃなくて、ひねくれててね(笑)。

北野 ひねくれ対二重人格(笑)。やっぱり外国を意識するとジャパニーズっていうのが入る。映画でもやっぱり「ちょんまげ」やってた方が喜ぶのはわかってんだけど、それやれる図々しさがあるかないかが勝負で。でも俺はやだっていうか、できない 。

山本 たけしさん、やんない方でしょ。

北野 やんない、やんない。

山本 僕もそれできないんですよね。

北野 本当のこと言うと、どこでやるかっていうのがあって、そのうち「秀吉」でもやってやろうかと思うんだけど(笑)、はなからそこへいくのはキタネエと思うよね。

山本 キタネェ(笑)。僕と川久保さんは、15年間ずっとヨーロッパの人から「モード・ジャポネ」って言われつづけてきて、時にはケンカしたくてきたんだけど、ようやく「もういいや」って感じでね。タブーがとれたから「着物」とかもやったりしてみたりね。

北野 フランスの映画週間に選ばれた時でも、ポスター見たら「サムライ」ってでっかく書いてあって、顔もでかく出てるのはうれしいけど、サムライじゃないんだけどなあ(笑)。何か、作られちゃうね。それじゃなきゃ評論のしようがないのかもしれない。入り口がね。今の時代、あまりに下品でストレートにやる連中が多すぎて、ちょっと照れること知ってやることすら、今の時代の中では「反逆」になる んじゃないかな。俺、おふくろがすごく厳しかった。「安売り」とか店に並んでる人見て、「いくら金なくったって、あんなことはすんじゃないぞ」って。みんな平気で並ぶじゃない。で、俺が「こんなの待ってられるかよ」って言うと、「どうして、そういちいち反逆するの?」とか言う。反逆じゃないって思うんだけど、もう世の中、主流が違ってきてるからね。世の中のある姿勢から見れば「なんてひねくれてんだろう」って思ってる人もいるだろうな。

堕落すること、落ちぶれることに対する憧れと、恐怖を持っていますか?

山本 淪落とか、堕落っていう言葉はカッコイイし、そうやって生きたいなって思うことはあるけど、なかなかできない。単純に、「落ちぶれる」っていう言葉の中にも、「貧乏」とか「食えない」っていう意味が含まれてるとしたら、それはばかばかしい。生きてりゃ、ちょっと何かやれば食えると思うんです。だから、本当に貧乏で食えないなんてばかばかしいですよ。

北野 「堕落」とか「落ちぶれる」とかロマンがあっていいんだけど、俺なんか図々しいから、みんなに見守られながら堕落しちゃうね(笑)。誰も見守ってくれないような堕落は嫌だっていうのは強い。だから、必ず保険を持ってるわけ。

山本 (笑)。

北野 この間、友達と話してて、「俺はなあ、やりたいことがあるんだ。中野の2万円のアパートで月20万でこれから一生暮らすのが夢なんだけど、まわりの人は俺のことなんて言うかな」って。その時思ったのは、あの人お金持ってるのになんであんなことしてるんだろうっていう落ちぶれはいいんだけど、「さもありなん」っていうのは嫌だよってことになった(笑)。

山本 やです(笑)。

北野 学生の頃、全国をほとんど乞食みたいな格好でヒッチハイクしながら全国歩き回るのに憧れた時があって、で、俺、熱海までヒッチハイクしたんだけど、熱熱海で「本物」に逢っちゃって、次の電車乗ってすぐ帰ってきた。「本物」にカツ丼おごってもらったりして(笑)。こりゃまるっきり違うわ。これには憧れねえな。俺にはスタミナもないしとか思った(笑)。

山本 たけしさんもそうだと思うけど、結局、普通のルールにのらない、反対だよっていうことでずっとやってるうちにこうなっちゃったわけだから。あらためて言わないけど、自分の中には、自分たちのルールというか、モラルがありますね。それが美学かな。

北野 年をとるっていうのは、当然、感覚も全部ダメになるなと思うし、怖いっていうのはあるけど、最近は割り切ってて、若い時なら集中力でやりとげたことが、長時間に変わるだけだろうって思うね。例えば、2時間で考えついたことを、ゆっくりと1日かけてやっていくような精神状態なんじゃないかな。きっと、自分が創ってく作品のグレードはそんなに変わんない。逆に言えば、若い時も、年とった時も、そんな変わったもんがつくれるわけじゃなくて、それにかける時間の配分が変わってくるだけなんだろうけど。瞬発力無くなったって言われればそうだよな。

あなたにとって「死」とは怖いものですか?

山本 死は怖いですよ。でも唯一、感覚的にわかるのは、細胞が衰えていて、壊れていくから死ぬんだってことですね。だってピンピンしてたら死ねないわけだから。僕の友達で酒で100年かけて自殺した奴がいて、時間かけすぎだけど(笑)。たけしさんはどうですか?

北野 人間って、快感としては、一方で「建設的」なことをやりながら、一方でそれをはずそうっていう勇気を持ってるぞっていう自信があると楽しいけど、それがなくなった時ってつまんない。つくるだけじゃなくて、やめたっていつ言うかを覚悟してる。それは、やっぱり、生きてることと同じことで、くたばってもしょうがないと思った瞬間から、生きるってことが楽しくなる。死にたくないって思いながら、生きてくことのつまんなさって、たまんねえだろうなあって思う。くたばる時は、くたばるって思った瞬間から、生きることが楽しくなるっていうかね。

山本 でも、年とってもみんなに好かれる老人にはなりそうにないですね、僕も、たけしさんも(笑)。

北野 だろうねぇ、あのジジイが来やがったとか(笑)。孫のこづかいをどうやってふんだくるとか。

山本 すっげえ恥ずかしいっていうか、4、5歳のガキの頃から、ずっと、「人生って大変なんだろうな」って思ってたんですよ。20代なんて戻りたくもないし、27~28歳の奴見てると、何かあくせく焦っててね、本当に気の毒だと思う。俺は子供の頃から人生なんて早く終わりにしちゃいたいってずっと思ってきましたから。それに、わがままにやってきたから、とにかく、「いいジイサン」とか絶対言われない、わがままやってきた報いがきますね(笑)。でも最後まで「しょうがねえなあ」って言われるまんまいくでしょう(笑)。

いい女にもてたいっていう気持ちは強いですか、いい女の条件は?

山本 何かいい女の条件を並べろって言われても一般論じゃ言えないなあ。「こいついいなあ」ってあっても、ヒトのカミサンだったりするし(笑)。でも、年とって「文化人」とか言われて暮らすより、女の人に好きだって言われる方が全然いいですよ。

北野 「文化人」って言われると、「ポコチン」が立ってはいけないんじゃないかって(笑)。

山本 立っちゃいけないんだよ。

北野 女の子はね、「ものすごいバカ」か、「頭いいか」のどっちかしかない。そのどっちにもつかない奴が一番面倒くさくって、イライラするんだよ、はっきりしてくれって。完全にバカか、ちゃんと頭切れてるんならつきあうのもおもしろいけど、真ん中は、団塊の世代と同じで、ダメ。

山本 僕は本当に母親の影響が大きかったんです、特に20代ぐらいまでは。若い頃見た悪夢には必ずといっていいぐらい、母親が着物をぞろっとだらしなく着て、垣根のところを狂って歩いているっていう夢でね。それが怖くて怖くて、でもしょっちゅう見ましたね。つきあう女の子にしても、全然母親とタイプが違ってると思ったら、どこか似てたり。

北野 そうなんだよね、俺も人格形成は、ほとんどお袋によってっていうか、お袋との「闘い」によってできた。どうやってお袋に言われたことに逆らい、だまして遊ぶかってことしか考えてなかったね。でも、いつの間にか、お袋の言いなりになってたり。結局、お袋っていうのは、子供がどんな悪いことしてても、とにかく最後まで更生させようとする。だから、自然と、女の人っていうのはいつも俺に注目してくれてるとばかり思っちゃう。2年ぐらい電話しなくったって、ガール・フレンドは絶対俺のこと待ってると思ってんのね(笑)。図々しいんだよね。そうじゃないんだってわかったの、最近だもん(笑)。

自分を笑うということについて、どう思いますか?

山本 もう20年ぐらい前なんだけど、自分の会社が有名になって成功した時に、母親に、「成功したのも、みんな冗談なんだから。本当にいつ潰れてもいいよね」って言ったんです。「これは冗談」って言ってないと、本当に笑われちゃうぐらいカッコ悪くなっちゃうから。「何ムキになってんの?」とかね。もう今の時代は、「一億総観客」だから。自分では何もしないのに、批判する側。フランスなんか特にそうで。だから、最初から自分をいつも笑ってないとね。

北野 最近思うのは、もっと笑わせるためには、もっと大きくなきゃできないなってこと。三船敏郎が、ひっくりかえるのは、その辺のおじさんがこけるよりおもしろい。つまり、小さな町工場が倒産したぐらいじやだれも笑わないけど、大会社が倒産した方がおもしろい。とんでもなくでっかいのが潰れるっていうと笑えるから。とにかく今あるのは、カンヌ映画祭で監督入場を断られたいって(笑)。「どうしてだめなんだ」って聞いたら、「格好が悪いから」じゃあって、ふんどしであらわれて、「これは日本の民族衣装だ」とか言ったりして。また、断られて、トロイの木馬であらわれて中から出てくるとか。それをするには、すげえ大監督じゃなきゃなと思う。「たけしがカンヌ入場、拒否される‼」っていうのは、今の時点では何のニュースにもならないでしょ。なぜ大監督になりたいかっていうと、入場を断られたいっていうだけで⋯⋯。笑われたいからね。

山本 (笑)ファッションももちろんアートじゃなくて、商売だけど、いつも会社にまるごとギャンブルしてるっていう感じでいたいなって思ってますね。コレクションって1年に4回やってるんです。男2回、女2回。その内のどれかでは、ギャンブルしちゃいますね。前の席の人たちがみんな立って帰っちゃったんじゃないかっていう思いでショウをやることもあります。でも、そうやっといて、次はウケてやろうとか思ったり。ウケるテクニックもすごくわかってますから、本当にもう自分がすごく嫌ですよ、ずるい奴(笑)。

北野 映画やってて『ソナチネ』なんてヨーロッパですごい評価になってうれしかったけど、そうすると次の作品も同じような映画だと喜ぶのがわかって嫌だから、『みんなやってるか?』みたいなめちゃくちゃな映画つくったり。それでも淀川さんとか、フランスの評論家とか「あれは傑作だ」とか言ってて、俺を苦しめるんじゃないって(笑)。こりゃ、めちゃくちゃ言われるだろうというのは実は内心では丁半バクチで、へたするととんでもない作品になる可能性もあるような部分もつくっとくからね。

山本 そうそう。振り子みたいにね。時代がちょっと変わった瞬間にマイナスがプラスになることがあるし。なんかずっとやってるうちに縁っていうか、崖っぷちにいつもいるんだなって思います。そう言うと、ちょっとよすぎて嫌だけど。選んでそういう風に自分から行きたかったわけじゃないですから。世界のデザイナーでも毎シーズン安定した、同じような服をつくるような人がいるんです。儀式みたいなショウをやってね。僕は、そういうのできないですもんね。そういうことができない育ち方だから(笑)。外国の評論家からはよく「エッジーな仕事してる」とか言われて、とりあえず、褒め言葉にとってますけどね。

北野 耀司さんと、話しするのは初めてなんだけど、なんかものをつくる人の理想的な屈折の仕方してると思うなあ。ちょっと歪んだやつつくれって言われても、耀司さんみたいには誰もつくれないと思う。それは心の問題だとしたら、見事な「ねじれ方の精神」っていうか(笑)。

山本 理想的な屈折か、いいな(笑)。

北野 崖っぷちってことで言うと、俺は崖のふちに立っている人じゃないね。匍匐前進みたいなかっこうで腹ばいになっていて、崖から下を見てるような感じ。立ちたいと思ってるんだけど、まだ絶対安全みたいなところにいて、立たないんだ。だってよろめいたらすっげえ怖いもん(笑)。

Do you think you guys might become targets of “Oyaji-gari” (attacks on older men by youth)?

Yamamoto: Even if someone calls me “oyaji” (old man), I just don’t see myself that way. I still see myself as an adult, and while people around me say I’m grumpy or difficult, those who really know me treat me like a kid. They don’t treat me like an adult at all. So, if you think about it, those delinquent kids grow up, but they stay delinquent kids even when they get old (laughs).

Kitano: My dad couldn’t even write his name and was always violent. When he came home, it felt like something dangerous had returned. We never really talked, and I don’t think we ever ate a single meal together.

Yamamoto: My dad was basically never there. When I was around a year and a half old, he was taken off to war and never came back. So, I never had a father. There was no image of a father in my mind. It was just my mother and me. Back then, there were many war widows.

Kitano: When I saw things on TV like “I love you, Dad,” it just rubbed me the wrong way. I thought, “What the hell is this?” But you know, even though my dad used to beat me and my mom all the time, one time when we went to Enoshima and I got a single Hershey’s chocolate from a foreigner, he made me sit on my knees at the station and say “Thank you” over and over. That’s when I thought, “Wow, America is powerful” (laughs).

Yamamoto: My family never had that typical “home” or “family” atmosphere at all.

Kitano: The dads right after the war—many of them had killed people in the war. You’d never think of attacking guys like that. Plus, when I was a kid, there were gangsters in the neighborhood, and we never stood up to them. They were all “oyaji.” Today’s youth don’t have any of that fear or respect for older guys. If you think about it, the only group that might still hold any kind of authority is the former student radicals, the “Zenkyoto” people. Like, “We fought each other with wooden poles.” But physically, if they actually fought 17- or 18-year-olds today, they’d probably lose. The illusion and the respect are just gone. Naturally, that leads to “oyaji-gari.”

Yamamoto: These kids today probably don’t have any memories of killing snakes or animals when they were little. So now, they’re turning on people instead—the weak ones.

Kitano: I don’t want to deal with young people. I don’t even want to talk to them. Honestly, I just hate them (laughs). People say, “The youth has a bright future,” but I hate that idea. The future has nothing to do with being young. You guys don’t have a future, period (laughs). It all depends on individual qualities. Maybe we’ll start seeing “kid-hunting” instead. Though probably no one would do it (laughs). Like pretending to call a girl from a telephone club, and then when the group shows up, a bunch of old guys surround them. That’d be ideal, don’t you think?

Yamamoto: In my 30s, I remember thinking banks were “scary,” but I never felt threatened by young people. I don’t get into fights often, but nowadays, kids in Shibuya often carry knives. Getting punched doesn’t scare me at all, but if someone pulls a knife, they need to be taught, physically, that’s not okay.

Kitano: You can’t teach kids “common sense” anymore—it has no weight. Instead of saying, “You shouldn’t do that,” it’s quicker to say, “I’ll punch you.” Violence hits both physically and emotionally at the same time. In my neighborhood, people fought all the time. Getting hit and hitting others was normal. Until high school, I’d never been outside of Ueno, but when I got to college and went to Ikebukuro’s underground mall, a guy from another school threatened me, and I froze. I thought high schoolers from Ikebukuro or Shibuya were incredibly tough, and just walking around town made me nervous. Eventually, I got used to it and thought, “Screw them, I’ll get my revenge,” but by then, they were gone (laughs).

Yamamoto: (laughs) I grew up right in the middle of Kabukicho, so I was surrounded by shady people. When I was a kid playing catch and the ball hit a black car, they’d yell, “You little brat!” and punch me. I hated adults who hit kids. But the GIs were amazing. Once, while practicing swings with a wooden sword, I accidentally hit a GI behind me. Even though his face turned red, he didn’t get angry. He just said, “It’s a kid; it’s okay.” Like you, Takeshi, I was surrounded by working women and gangsters growing up, so I didn’t find any of it impressive. I never looked up to them. Shinjuku never scared me, but Ikebukuro did.

Do you feel discomfort or resistance being labeled part of the “baby boomer generation”?

Kitano: People often lump me into the “baby boomer generation,” but really, there were so many of us that there were all kinds of people—so much potential. My junior high had 16 classes, each with 60 students—1,000 per grade. The real bad guys were truly bad. Guys who were like gang leaders back then are actual yakuza bosses now. The smart ones went to Tokyo University and became professors at MIT. There’s a huge gap. But in the middle were the “so-so” guys, and they’re the ones now called the “mainstream” of the baby boomers.

Yamamoto: Like Takeshi said earlier, people are individuals—it’s not about their generation. I don’t think in terms of generational labels, and I don’t like that way of thinking. Foreigners often talk about “generations” or “cultures of the decades,” but I don’t get that.

Kitano: When people look back on the Showa-era entertainment world, I hate the idea that I’ll be lumped in with someone like Enoken. If you say “baby boomer,” the individuality disappears. Recently, I laughed at this: people say postwar Japanese live long lives, but those who are 80 now were born in the Taisho era. Anyone born after the war is only around 50. So to say they’ve lived long lives is weird. Generational groupings don’t make sense (laughs).

Do you feel discomfort with the current era? Or do you feel detached from it?

Yamamoto: Lately, I feel like I’ve started to decline a bit (laughs). Time is what stretches from your birth to your death, right? If life lasts only 50 or 60 years, you start to feel a sense of attachment to the people you shared that time with, like, “We did this together.” That’s when I think, “Yeah, I’m getting old.”

Kitano: When I think about it, I’m smack in the middle of the baby boomer generation. I hated that. I couldn’t be above or below—it was frustrating. So maybe my frustrations were directed at my own generation. Even if I didn’t consciously think about it, I was fighting with them. When the media calls out “baby boomers,” I realize I’ve always been part of that generation, but seeing it in print makes me think, “These guys live totally different lives from me.” It hits me now: “So these are the baby boomers.”

Yamamoto: Before discomfort, I always felt that “all males are the enemy.” It was just me and my mother. I wasn’t as extreme as Dazai Osamu, but I saw the world through women. At kindergarten, all the other kids had scalp fungus and boils, while I had a clean haircut and my mom dressed me fashionably—I was totally alone. That feeling of isolation was my foundation. Everyone around me was an enemy, nothing more. The gap never closed.

Kitano: I think it’s the same for you, Yohji—when you’re in business, you can’t just cut off your audience completely. But at the same time, there’s a fence—you can’t let them in. Without a target audience, you can’t make a living. If you don’t have the guts to cut them off, it eats at you and gets frustrating.

Yamamoto: What gets to me lately is when junior high or high school students come up to me saying, “Yohji-san, can we shake hands?” or “This kid’s a big fan, can you give them an autograph?” That’s just a misunderstanding. There shouldn’t be any connection between us, but they ask for handshakes anyway. Honestly, I’m doing something totally different now, and I wish they’d get that (laughs).

Kitano: When I’m working and on edge, and I go perform at a theater, there’s always someone in the audience who clearly doesn’t want to laugh at me. Like, “Don’t you dare make me laugh” (laughs). But comedians are supposed to make people laugh, right? I used to think, “As long as they laugh, it’s fine.” But after a while, it starts to bug you. Once, a yakuza in the crowd said, “Yakuza shouldn’t laugh,” and I had to escape out the back door (laughs). Same in Yohji’s world—some people want to be in the industry just to be called a designer. Some comedians only got in because they liked the word “entertainer.”

Yamamoto: There were tons like that. Since the time I started, if you threw a rock at the Harajuku intersection, you’d hit a wannabe designer.

Kitano: Yeah, for them, the goal is just to be called a designer. All young people start that way.

Yamamoto: I often can’t tell if people who approach me are drawn to the image of being a designer, or if they actually like me as a person. And that makes me want to do something reckless. My goal in life is about how to do something reckless. I never had a dream like, “I’ll become a world-famous designer.” If you’ve got good instincts, you’d realize how dull this industry actually is. It’s way better to live with a cool woman and feel excited every day (laughs). Being a designer is like building a “castle of mystery” (laughs). But I always try not to finish it. I try to do the uncool stuff on purpose.

Kitano: I sometimes feel like I have a split personality. I created this “Beat Takeshi” persona, and I feel like I’m just friends with him. I’ll drink alone and say to myself, “You’re such an idiot.” It’s like I’m playing with a puppet version of myself. But once you fuse too tightly with that puppet, you get stuck. When things aren’t going well, it’s not really me. But when the puppet starts moving well again, I slip back into it, conveniently.

Some people in the world—like bureaucrats—are sly or devious. You’re not like them, but do you have a sense of “cunning” or “badness”?

Kitano: I feel like I have two selves. Even if one side creates something and everyone praises it, I’m only half-happy. Watching one half of myself do something doesn’t give me the same joy as doing it all by myself. It’s only about half as satisfying.

Yamamoto: People used to tell me that a lot—especially fashion journalists. “Yohji, you should throw yourself completely into one thing.” But I just can’t. I’m too detached. When I decided to do my first show in Paris, I was determined not to show Japanese kimonos or anything. I wanted to do it using European methods. Every other Japanese designer brought something traditionally Japanese. I based my show on how Portuguese people dressed when they first came to Nagasaki before the Meiji era. There are just so many things I can’t do because I get embarrassed. It’s not just being shy—it’s because I’m twisted (laughs).

Kitano: Twisted versus split personality (laughs). When you think about foreign audiences, you inevitably lean into your Japanese identity. With film, too, I know people enjoy it more when there’s a “chonmage” (samurai topknot), but I just don’t have the guts to do that. I don’t want to.

Yamamoto: You’re the type who doesn’t do that kind of thing, right?

Kitano: Nope, never.

Yamamoto: I can’t either.

Kitano: Honestly, I might try something like “Hideyoshi” someday, but to jump straight into that from the start feels cheap.

Yamamoto: Gross (laughs). Kawakubo and I have been called “mode Japonaise” by Europeans for 15 years. At times, I wanted to argue with them, but lately I’ve just felt like, “Whatever, it’s fine.” Once that taboo was gone, we started trying things like incorporating kimono.

Kitano: Even when one of my films was selected for the French Film Week, the poster had “Samurai” in huge letters. I mean, my face was big on the poster too, and that was nice, but I’m not a samurai (laughs). It’s like people always have to fit you into some mold. Maybe they have no choice—it’s the only way they can make sense of you. These days, there are so many people doing things so crudely and straightforwardly that even just doing something with a hint of restraint feels like rebellion. My mom was super strict. When she saw people lining up for discount sales, she’d say, “No matter how broke you are, don’t ever do something like that.” But people just line up without thinking. And when I said, “I can’t wait in line for this,” she’d say, “Why do you have to rebel all the time?” I didn’t think it was rebellion. But society’s mainstream has shifted. So I’m sure some people look at me and think, “Man, what a contrarian.”

Do you have a fascination with or fear of corruption, of failure?

Yamamoto: Words like “depravity” or “corruption” sound kind of cool, and sometimes I think I’d like to live like that, but it’s not that easy. If “failure” includes “poverty” or “not being able to eat,” that’s just silly. As long as you’re alive, you can do something and get by. So real poverty, real hunger—it’s ridiculous.

Kitano: Yeah, “corruption” or “failure” has a certain romance, but I’m so shameless I’d probably fall into depravity while still being watched and cared for (laughs). I don’t want to fall into obscurity where no one notices. That’s why I always have a safety net.

Yamamoto: (laughs)

Kitano: I was talking to a friend recently and said, “I’ve got this dream. I want to live the rest of my life in a ¥20,000-a-month apartment in Nakano on a ¥200,000-a-month income. But what would people around me say?” And I realized, it’s okay if people say, “He’s rich, why is he living like that?”—but I’d hate it if people just thought, “Well, of course he ended up like that.” (laughs)

Yamamoto: Yeah, that’s the worst (laughs).

Kitano: When I was a student, I had this romantic notion of hitchhiking all around Japan, dressed like a beggar. I actually hitchhiked to Atami once—but there, I ran into a real homeless guy. He even bought me a pork cutlet bowl. I got right back on the train and went home (laughs). I realized, this isn’t what I want. I don’t have the stamina for that life (laughs).

Yamamoto: I think it's the same for you, Kitano. We’ve ended up here by always refusing to play by the normal rules. I don’t say it outright, but I definitely have my own internal rules—my own sense of morality. Maybe that’s what you’d call aesthetics.

Kitano: Growing old is scary—you feel your senses starting to dull—but lately I’ve come to terms with it. When I was younger, I could get things done through sheer concentration. Now it just takes longer. Like, something that took me two hours to think through before might now take a full day. But I don’t think the quality of what I make will change much. In fact, whether you’re young or old, your work doesn’t change that dramatically—it’s just how you manage your time. If someone says I’ve lost my quick instincts, yeah, maybe they’re right.

Is “death” something you fear?

Yamamoto: Yeah, death is scary. But the only thing I can grasp intuitively is that your cells weaken and break down—that’s what leads to death. If you’re still full of life, you just can’t die. I had a friend who basically spent 100 years drinking himself to death—talk about taking your time (laughs). What about you, Kitano?

Kitano: I think for humans, it’s enjoyable when you’re doing something constructive, while also feeling like you’ve got the guts to throw it all away if you want to. But once you lose that feeling, it gets boring. It’s not just about creating—knowing you can stop is part of it too. That moment when you think, “It’s okay if I die now,” that’s when life becomes fun again. Living while thinking “I don’t want to die” sounds miserable to me. But if you’ve accepted that dying is fine, suddenly life becomes a lot more enjoyable.

Yamamoto: But neither of us is ever going to be that lovable old man, are we? (laughs)

Kitano: No way. People are going to be like, “Oh great, that old guy showed up again.” Trying to scam pocket money from our grandkids or something (laughs).

Yamamoto: I’ve been embarrassed all my life. Even when I was four or five, I had this sense that “life must be really hard.” I have no desire to go back to my twenties. When I see people around 27 or 28, they’re rushing and panicking, and I feel bad for them. I’ve always felt like I wanted life to end early. And since I’ve been selfish all along, I’ll get what’s coming to me—I’m definitely not going to be called a “nice old man” (laughs). But I’ll probably just keep going with people saying, “Well, that’s just how he is.” (laughs)

Do you have a strong desire to be popular with attractive women? And what makes a woman “attractive” to you?

Yamamoto: I can’t really lay out some general “criteria” for a good woman. Even if I meet someone and think, “Damn, she’s great,” turns out she’s already married or something (laughs). But honestly, I’d much rather be told “I love you” by a woman than be called an “person of culture” as I get older.

Kitano: Yeah, when people start calling you a “person of culture,” it feels like your dick isn’t allowed to get hard anymore (laughs).

Yamamoto: Exactly, your dick’s not supposed to get hard.

Kitano: When it comes to women, they’re either really dumb or really smart—there’s nothing in between. And the ones stuck in the middle, the ones who are neither, those are the biggest pain in the ass. They’re annoying as hell. I just want them to make it clear already. If she’s totally dumb or clearly sharp as hell, it’s actually fun to be with her. But the ones in the middle? They’re like the baby boomers—totally useless.

Yamamoto: My mother had a huge influence on me—especially up through my twenties. In almost every nightmare I had when I was younger, she’d show up in this loose, sloppy kimono, wandering around like she was insane near the garden fence. It terrified the hell out of me. I used to see that dream all the time. And even with girls I dated, I’d think they were totally different from my mother, but then I’d realize there was always something about them that reminded me of her.

Kitano: Yeah, same here. My whole personality was basically shaped by my mom—or more like, by the battle with her. My life was all about figuring out how to rebel against her, how to trick her so I could go out and mess around. That was my whole strategy. But somehow, without even realizing it, I’d end up doing exactly what she said anyway. In the end, no matter how bad her kid was, a mother will always try to rehabilitate him. She’ll never give up. And because of that, I just naturally came to believe that women are always paying attention to me. Like, even if I didn’t call my girlfriend for two years, I’d think, Of course she’s still waiting for me. (laughs) I was ridiculously full of myself. I only recently figured out that’s not how it works (laughs).

What do you think about laughing at yourself?

Yamamoto: About 20 years ago, when my company became famous and successful, I told my mom, “It’s all just a joke anyway. It could crash any time and that’d be fine.” If I don’t think of it that way, I’ll get laughed at for real—it’d be embarrassing. Like, “Why are you taking this so seriously?” These days, everyone’s just an audience. Nobody does anything—they just critique. France is especially like that. So I always try to laugh at myself first.

Kitano: I’ve come to feel that in order to make people laugh, you have to be huge. When someone like Toshiro Mifune falls over, it’s funnier than a regular guy tripping. Like, no one cares if a tiny factory goes bankrupt. But if a huge company collapses, that’s funny. I want to get so famous that I get rejected from Cannes. Show up in a fundoshi and say, “This is traditional Japanese wear!” Then come back riding inside a Trojan horse. But to pull that off, you have to be a legendary director. Right now, if “Kitano denied entry to Cannes” happened, it wouldn’t even be news. I just want to be laughed at—that’s why I want to become big.

Yamamoto: (laughs) Fashion is obviously a business, not art. But I still want my whole company to feel like we’re constantly gambling. We do four collections a year—two men’s, two women’s. I always gamble on at least one. Sometimes I do a show wondering if everyone in the front row is going to stand up and walk out. But then next time, I’ll try to be a hit. I know exactly how to make things popular—that’s why I hate myself. I’m so sneaky (laughs).

Kitano: Same for me with films. Sonatine got huge praise in Europe, which made me happy—but I knew if I made a similar movie next, they’d love it too, and that annoyed me. So I made something totally insane like Getting Any? And even then, people like Yodogawa or French critics said, “It’s a masterpiece.” Don’t torment me like that (laughs). I deliberately include parts that could totally flop—it’s a gamble every time.

Yamamoto: Exactly. It’s like a pendulum. If the timing is right, even a minus can turn into a plus. Doing this work, I’ve realized I’m always on the edge. It sounds a bit too cool to say it like that—I didn’t choose this path intentionally. Some designers produce safe, ceremonial shows every season. I just can’t do that. I wasn’t raised that way (laughs). Critics often say my work is “edgy.” I just take that as a compliment for now.

Kitano: Yohji-san, this is our first conversation, but I think you’ve got the ideal kind of creative distortion. Even if someone told others to make something weird, no one could do it quite like you. If it’s a matter of the heart, then you’ve got this beautiful “twisted spirit” (laughs).

Yamamoto: “Ideal distortion,” I like that (laughs).

Kitano: As for being on the edge, I’m not really standing at the cliff. I’m more like belly-crawling to the edge, peeking down. I want to stand up, but I’m still in the “totally safe” zone. Standing is scary—I might stumble and fall (laughs).

“BROTHER” Promotional Pamphlet

©2000 LITTLE BROTHER, INC.

Published and distributed by SHOCHIKU

Edited by HOUGADO Corp.

Designed by LEE CHUL SUP

Original photo for the book by SATOSHI MINAKAWA, ATSUSHI KIMURA (styling), YASUHIKO MIZUTANI (make-up)

Still photographer (U.S.A.) by SUZANNE HANOVER

Still photographer (JAPAN) by SATOMI SAITO

Additional stills by MASAYUKI MORI and TOSHIO WATANABE

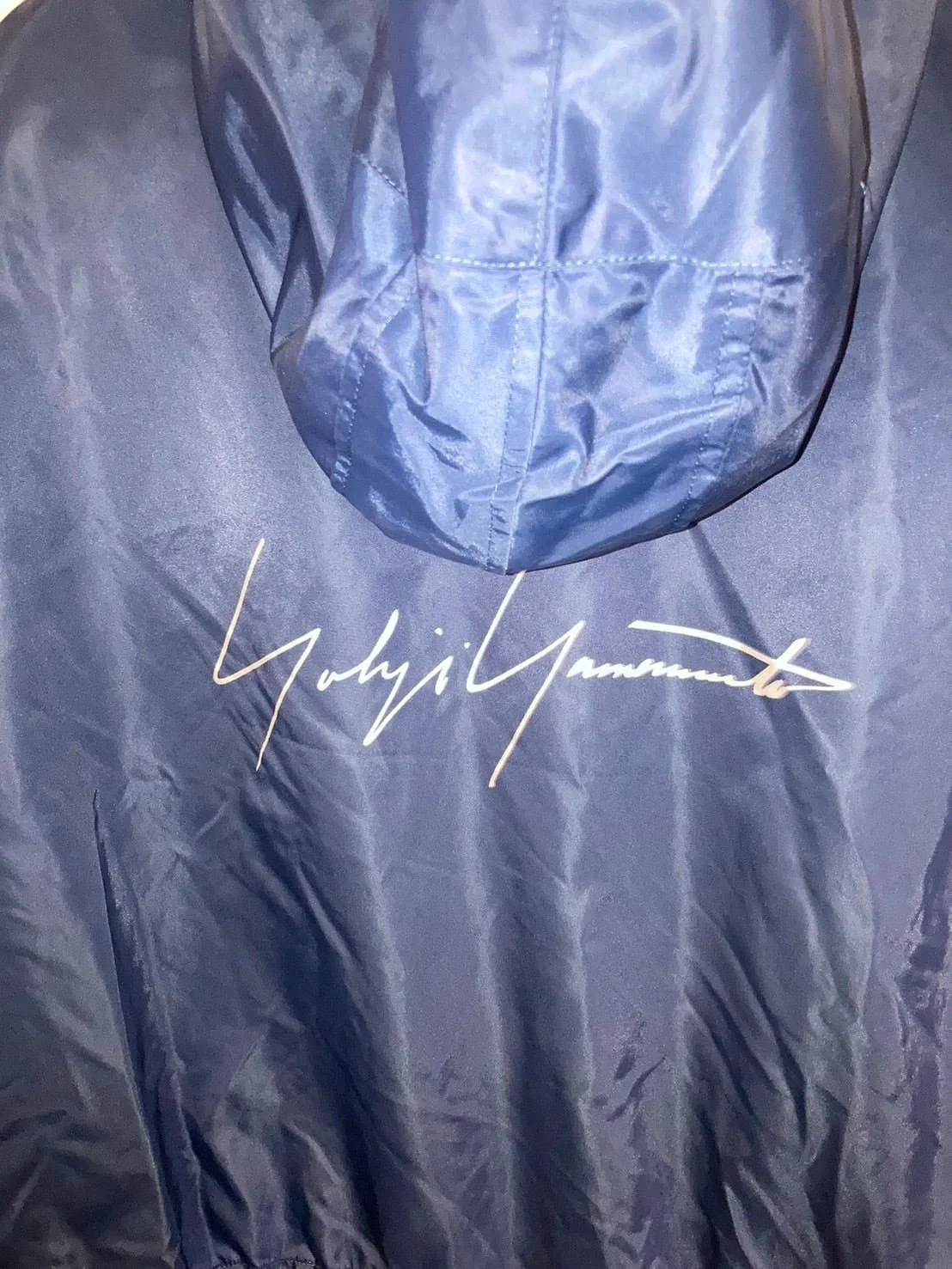

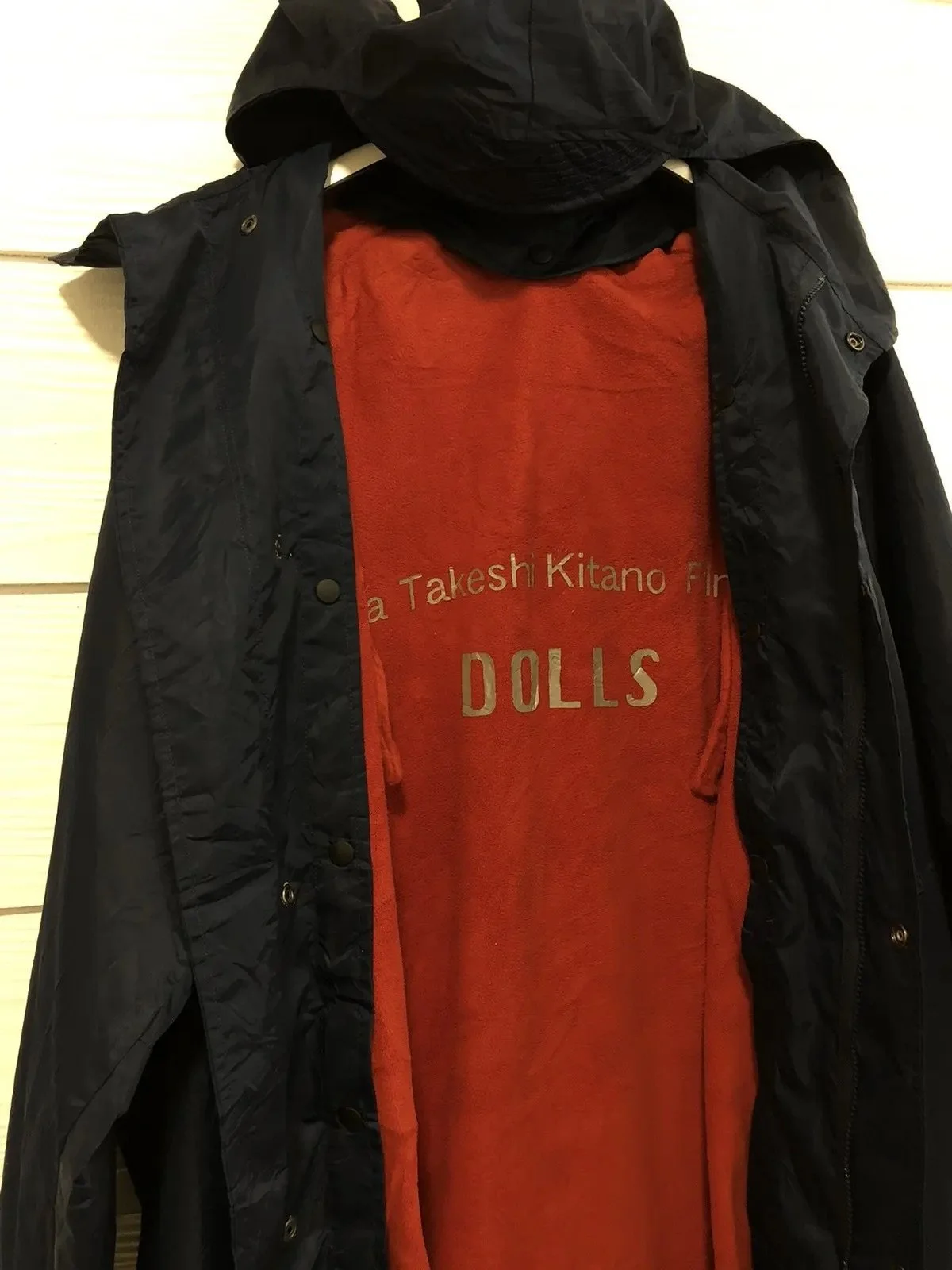

Thanks to Yohji Yamamoto inc.

Printed by TAIYO PRINTING

THAT’S BROTHER

December 2000

コマネチ!2

Published by Shinchosha Publishing Co, Ltd

Written by Yohji Yamamoto

Photography by Masayuki Mori, Junichi Iju, Suzanne Hanover, Toshio Watanabe, and Masami Saito

ヨウジ・ヤマモトのファッション・ページから、マネージャー・イヨリのお笑いページまで。スクリーンの表も裏も徹底研究。読んでから観るか、観てからまた読むか。映画を100倍楽しむためのコマネチ!流、〝BROTHER〞解体新書。

From Yohji Yamamoto’s fashion pages to Manager Iyori’s comedy pages: an in-depth exploration of both the front and back of the screen. Will you read before watching, or watch first and then read again? The コマネチ!-style breakdown of Brother, to enjoy the film 100 times more!

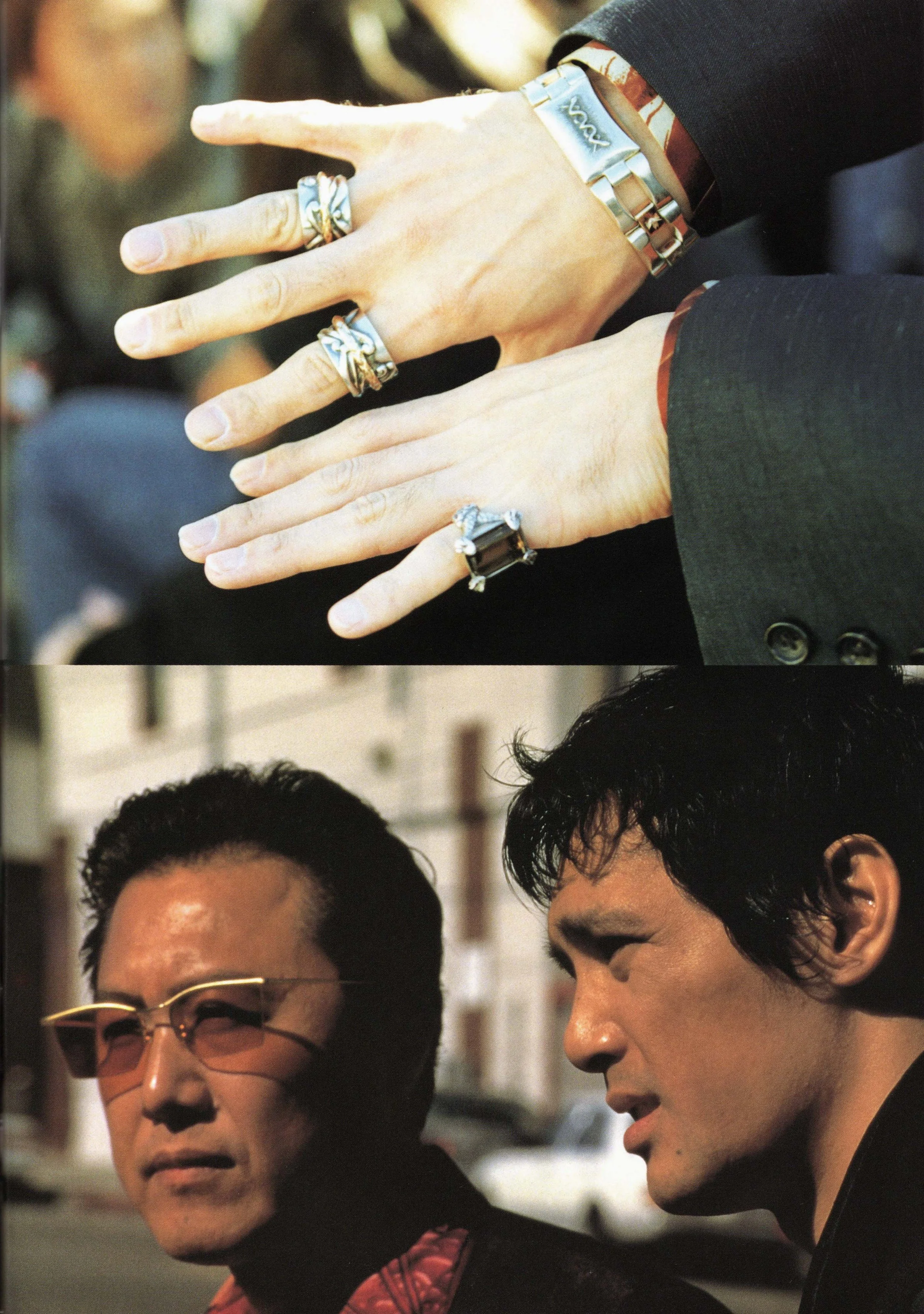

日本での撮影現場を訪れた山本耀司。最近はテレビ番組などでも、ビートたけしの衣装を手がけている。1月に行われる「21世紀の北野武展」(詳細はP185)では、映画で使われた衣装、アクセサリーも展示される。

Yohji Yamamoto visited the filming location in Japan. Recently, he’s also been designing Beat Takeshi’s outfits for TV programs and more. At the “Takeshi Kitano of the 21st Century” exhibition in January (see page 185 for details), costumes and accessories used in the film will also be on display.

二人の「山本」

山本耀司

「これ『コマネチ!2』の企画でしょ?じゃあ、真面目に答えるのヤメた」ビートたけし演じる「山本」をはじめとするメインメンバー8人の衣装を手がけ、『BROTHER』を陰で支えた世界的ファッション・デザイナー、山本耀司は、開口一番、そう言った。世界で活躍する2人が表現したかったものは、いったい何だったのだろう。

『HANA-BI』の後、ある雑誌でたけしさんと対談をしたんです。その時に少し『BROTHER』の企画について聞きました。それでしばらくしてから、ばったり飲み屋で遭遇した。たけしさんもかなり酔っ払ってて、僕もずいぶん酔ってたからよく覚えてないんだけど、衣装をやるとかそういう話になったのかな。何日か経って、オフィス北野の森社長から電話があって、「耀司さんが衣装を担当してくれるって北野が言っているんですが本当でしょうか」ってスタッフに尋ねられた。でも事務所のスタッフは初耳だから、ビックリして僕のところに確認しにきたわけ。「どういうことでしょうか?」と。だから「うん、やることになってるんだよ」って、そんなふうに始まりました。

去年、パリコレクションが終わってから、北野組のスタッフと初めて顔合わせをしました。マイノリティを集めてのしあがって、ある程度の組織になった時に白いリムジンに乗るという話を聞いて、最初はそのリムジンに乗っているシーンの衣装だけを依頼された⋯⋯というような記憶があります。成り上がって、今まで金なかったのが急に極端なおしゃれをする、そういうところはデザイナーがやらなきゃいかんなって僕も思った。そのうち加藤雅也さんに石橋凌さんと、後で組に加わる人たちのもやろうと、自然とそうなっていった感じですね。

初めはたけしさんがどういうものを欲しがっているか、イメージしているかを読むことが大変だったな。僕自身としては、フアッション・ショーは絶対やらないぞってことがテーマでした。つまり衣装が主張しちゃいけない、洋服のデザインが邪魔をしちゃいけないってことです。気が付いたら映画のムード、スピリットを支えてた、というくらいがちょうどいい。ヨウジ・ヤマモトっぽさなんていらない。誰がやったのか分からないくらいにしよう、と思った。だって日本で失敗した人が、アメリカで自分だけの力でのし上がるわけでしょ?そういう人がはなっからデザイナーズ・ブランドを着てたらまずいわけですよ。

難しかったのは、悪っぽさを出すことでしたね。昔は、野球選手とやくざはベルサーチを着てた。でもそういう分かりやすい悪っぽさじゃなくて、結構ふつうの背広感覚で悪っぽさ出すっていうのは、やっぱりボディ・フィットが重要になってくる。ちよっとずれてるって感じにしたいんだけど、その加減が微妙なんです。

ヴィム・ヴェンダースとの失敗で得たもの

僕は、過去にヴィム・ヴェンダースの『夢の涯てまでも』という映画に携わったことがあるんだけど、それはすごくリッチな映画でした。アイルランドのU2というバンドに音楽を頼んだり、僕に衣装をというふうに作ったわけ。合計500着くらいデザインしたんだけど、やりながら、大丈夫かなあって思ってたんです。ヴィムの映画って、それまで非常に限られた厳しい条件のなかで彼独特の深いことを、ちょっとドイツ人的な、くどくどしたしつこさで表現してきたわけじゃない?ところがその映画はゴージャスで、みんなもヴィムならって協力するんだけど、僕はやばいって感じた。ある日、新宿のパークハイアットにヴィムを迎えに行って、高速を走ってたら車の中でぼそっと言うわけですよ。「おまえにもあるだろ、これは失敗だって思ってても終わらせなきゃいけないものって」、と。「うん、俺にもある」って答えたきり、あと2人でシーンとしちゃって⋯⋯。案の定、映画は大失敗。そのときの痛烈な思い出があるので、いかにも有名なファッション・デザイナーがやりましたっていう、飾りたてたものは今回はやらないと決めた。

たけしさんにとって『BROTHER』は一種の大勝負に出たわけでしょ?ハリウッドに乗り込んで、今までとは違うパターンで作って⋯⋯。それはやっぱりギャンブルですよね。でも北野組の一員としてはね(笑)、ヴィムのような失敗はしてほしくなかった。この間のベネチア映画祭で「ファッキング・ジャップくらい分かるよ、バカ野郎」って台詞が大ウケして、最後に観客が総立ちで拍手したってたけしさんに聞いた。例によって僕たち2人は酔っぱらってそんな話をしてたんだけど、あんな嬉しそうなたけしさんを見たのは初めてだったな。成功したんだというのが、僕もほんとうに嬉しかったです。その後で会った時にはずいぶん髪が短くなって、雰囲気が変わってて、切り替え早いなって思った。もう次に行ってるんだな、って。要するにつかまえられない男なんですよ。つかまえたと思っても、するりと逃げられちゃう。もう次の映画の話もしてますよ。まだ秘密ですけど――。

The two “yamamoto”

Yohji Yamamoto

“This is for the コマネチ!2 project, right? Then I’m not going to answer seriously,” said Yohji Yamamoto right off the bat, the world-renowned fashion designer who supported Brother behind the scenes and designed the costumes for the eight main cast members, including Beat Takeshi's character, 'Yamamoto.' What on earth were these two world-famous actors trying to express?

After HANA-BI, I did an interview with Takeshi-san in a magazine. At that time, he told me a bit about the Brother project. Then sometime later, we happened to run into each other at a bar. Takeshi-san was pretty drunk, and I was too, so I don’t remember much, but I think we talked about me doing the costumes or something like that. A few days later, I got a call from Mr. Mori, the president of Office Kitano. He asked my staff, “Is it true that Yohji-san will be handling the costumes? That’s what Kitano is saying.” But my staff had never heard about it and were shocked—they came to me to confirm, like, “What’s going on?” So I said, “Yeah, I’ve agreed to do it.” And that’s how it all started.

Last year, after Paris Fashion Week ended, I met the Kitano team for the first time.

I remember hearing about this scene where the characters, having risen up as a minority group and become a semi-organized force, ride in a white limousine. At first, I was only asked to design the costumes for that limousine scene… or at least that’s how I remember it. These were guys who used to have no money, but suddenly they were dressing in flashy, extreme styles after climbing up in the world. I felt that was exactly the kind of thing a designer needed to handle. Then, as things developed, it naturally turned into also doing outfits for people like Masaya Kato and Ryo Ishibashi—characters who would later join the gang.

In the beginning, it was difficult to decipher what kind of look Takeshi-san wanted, or what image he had in mind. For me, the main theme was that this is not going to be a fashion show. In other words, the costumes shouldn't stand out, and the design shouldn't interfere. Ideally, you’d only notice later that the costumes had helped support the film’s mood and spirit. There was no need for any “Yohji Yamamoto-ness.” I wanted people to watch it and not even know who did the clothes. After all, the story is about a man who failed in Japan and then claws his way up in America purely on his own strength, right? It wouldn’t make sense if someone like that was wearing designer brands from the start.

The hardest part was bringing out a sense of “toughness” or “edge.” Back in the day, baseball players and yakuza would wear Versace. But that’s too obvious. We wanted to bring out that toughness using something more subtle—like an ordinary suit. That meant getting the fit just right was really important. I wanted it to feel slightly off—just a little strange—but getting that balance was really delicate.

What I Gained From My Failure With Wim Wenders

In the past, I worked on Wim Wenders' film Until the End of the World. It was an incredibly lavish production. They had the Irish band U2 doing the music, and I was brought on for the costumes. I designed about 500 outfits in total. But as I was working, I kept thinking, Is this really going to be okay? Wim's previous films had always been created under strict limitations, where he would express deep, complex ideas in a very German, meticulous, persistent kind of way. But this film was all glamor. Everyone was willing to help because it was Wim, but I felt like it was heading for trouble. One day, I went to pick Wim up at the Park Hyatt in Shinjuku. While we were driving on the expressway, he suddenly muttered in the car, “You’ve had this happen too, right? Where you know something’s a failure, but you still have to see it through to the end.” I replied, “Yeah, I’ve had that too.” Then we both just went silent… Sure enough, the film turned out to be a huge failure. That experience left a strong impression on me, so this time I made up my mind not to create something showy that screams “a famous fashion designer did this.”

For Takeshi-san, Brother was a major gamble. He went to Hollywood and made a film in a completely different style from his previous work. That’s definitely a risk. But as a member of the Kitano crew (laughs), I didn’t want him to experience a failure like Wim did. At the Venice Film Festival the other day, I heard from Takeshi-san that a line—“I understand ‘fucking Jap,’ you asshole”—got a huge laugh, and in the end, the whole audience gave a standing ovation. As usual, we were drunk while talking about it, but I’d never seen Takeshi-san look so happy. I was really happy too—it felt like a real success. When I saw him again after that, his hair was much shorter, and his whole vibe had changed. I thought, He’s already moved on. That’s just the kind of man he is—you can’t pin him down. Even if you think you’ve caught him, he slips right through your fingers. And yes, he’s already talking about his next movie. Still a secret, though.

Yohji Yamamoto

1943年東京生まれ。’66年慶応義塾大学法学部卒業。’69年文化服装学院デザイン科卒業。’72年、(株)ワイズ設立。’84年、(株)ヨウジヤマモト設立。’77年東京コレクション、’81年パリコレクションに作品を発表し、世界的に注目されるデザイナーとなる。以後、フランス芸術勲章、CFDA賞(米)など国内外で数々の賞を受賞している。

Yohji Yamamoto

Born in Tokyo in 1943. Graduated from Keio University’s Faculty of Law in 1966. Graduated from Bunka Fashion College’s design program in 1969. Founded Y’s Co., Ltd. in 1972, and Yohji Yamamoto Co., Ltd. in 1984. Debuted his work at Tokyo Fashion Week in 1977 and Paris Fashion Week in 1981, gaining international recognition as a designer. Since then, he has received numerous awards both domestically and internationally, including the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and the CFDA Award (USA).

山本

ビートたけし

たけし自身の希望により、スーツの色は紺、シャツは開襟のものをぺらっと着ている雰囲気で統一した。一見、すべてのシーンで同じスーツを着ているように思われるが、微妙に色の濃淡が異なるものを日本で二種類、ロスで二種類、着替えている。

スーツのかっこよさは袖丈と上着丈の差で決まる。上着丈が短すぎるとサラリーマンふうになってしまうため、数ミリ単位で長さにこだわった。

リムジンシーンのために用意されたストライプのスーツ。結局、土壇場で着用しないことになった幻の一着。

ロスでは、到着時と中盤以降のシーンで違うスーツを着用。こちらは中盤以降で、シャツもブルーに。

Yamamoto

Beat Takeshi

At Takeshi’s own request, the suit color was unified as navy, and he wore an open-collar shirt to give a relaxed feel. At first glance, it looks like he’s wearing the same suit in every scene, but in fact, there are subtle variations in shade—two suits in Japan, and two in Los Angeles, that he changes between.

The coolness of a suit is determined by the difference in sleeve length and jacket length. If the jacket is too short, it gives off a “salaryman” vibe, so they paid careful attention to the length down to the millimeter.

There was a striped suit prepared specifically for the limousine scene. In the end, he didn’t wear it, making it a phantom outfit.

In Los Angeles, he wears a different suit upon arrival and another one for the latter half of the scenes. In the latter half, the shirt is also blue.

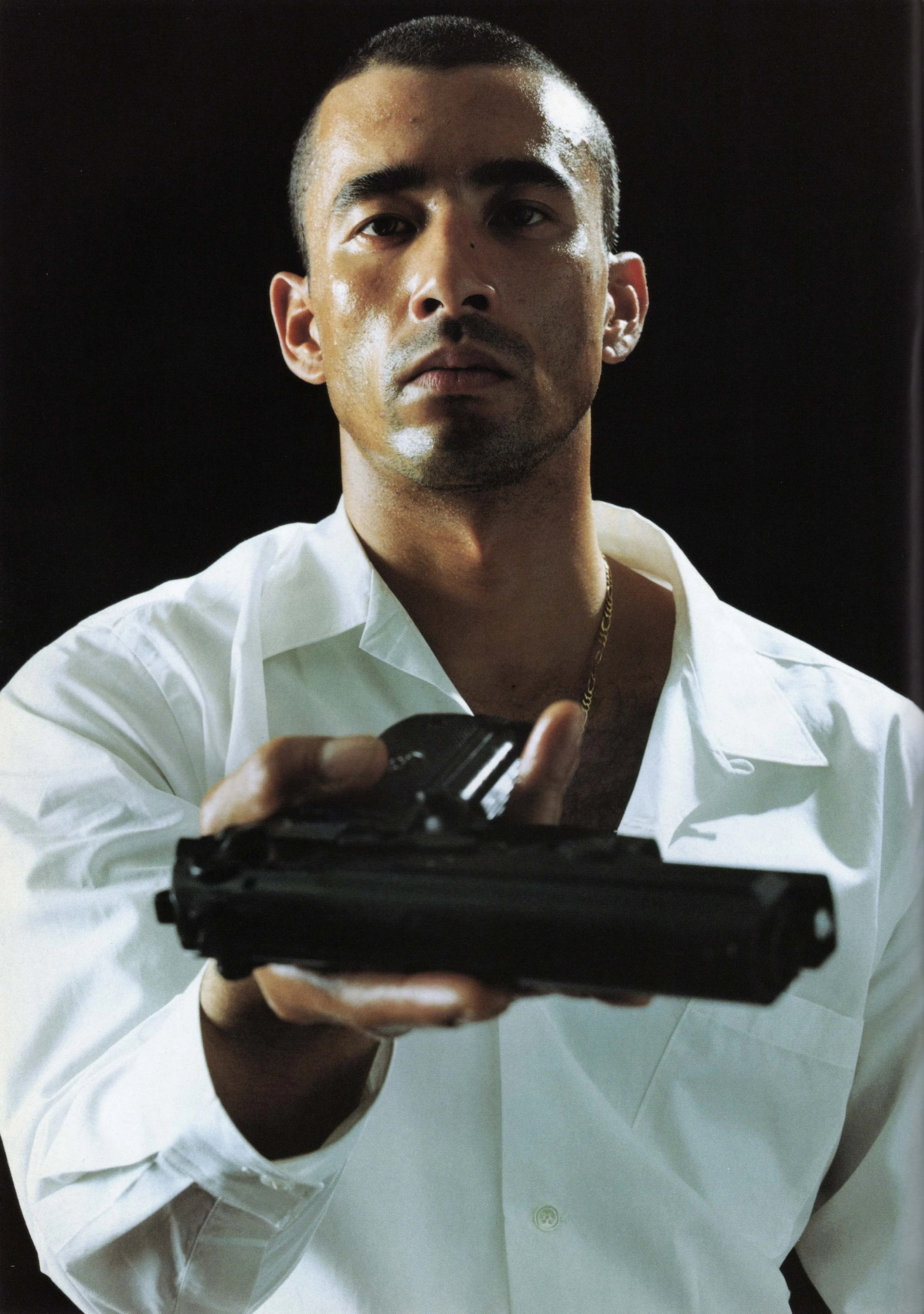

ケン

真木蔵人

何を着せても似合いすぎてしまうため、デザインにもっとも苦労した役者の一人。特に麻薬売人時代のストリート・ファッションとは一変、途中からスーツを着るため、役柄のイメージにギャップを感じさせないよう、だらしなさを表現する工夫が必要だった。

(左)山本のスタイルを真似て、白の開禁シャツを着用。スーツは濃紺。襟の幅を広めにとると、華やかさが増す。この時だけは靴が黒。ネックレスのチェーンと財布のチェーンがおそろい。

(右)上着の袖丈を 長めにし、パンツの裾も ひきずるくらい長くすることで、だらしなさを強調した。生地もよれよれ感が出るものを使用。

「ちょっと派手にしても似合うので、成り上がった時くらいはいいだろう」と襟元にライトブルーを添えた。

登場人物のなかでは、もっとも小物にこだわっているのがケン。ベルトと靴も蛇革でそろえている。

物語後半の組織が危ない状態になった時は、地味で、くたびれた雰囲気に。真木はおち、ぶれた様子を表現するのがうまい!

Ken

Claude Maki

Because he looked good in anything, he was one of the most challenging actors to design for. Especially because his character transitions from a drug dealer in street fashion to wearing suits partway through, it was important to express a kind of sloppiness to avoid creating a jarring shift in his image.

(Left) Mimicking Yamamoto’s style, he wears a white open-collar shirt. The suit is dark navy. A wider collar adds a sense of flair. This is the only time he wears black shoes. His necklace chain and wallet chain match.

(Right) By making the jacket sleeves longer and the pant legs almost drag on the floor, the design emphasized his careless appearance. The fabric was also chosen to give a worn-out look.

“We made it a bit flashy since he could pull it off—figured it was fine for when his character rose in status,” they said, adding a touch of light blue to the collar.

Among all the characters, Ken was the most particular about accessories. His belt and shoes were coordinated in snakeskin.

When the organization starts to fall apart in the latter half of the story, his look becomes plain and worn-out. Maki did a great job expressing his character’s sense of loss and instability!

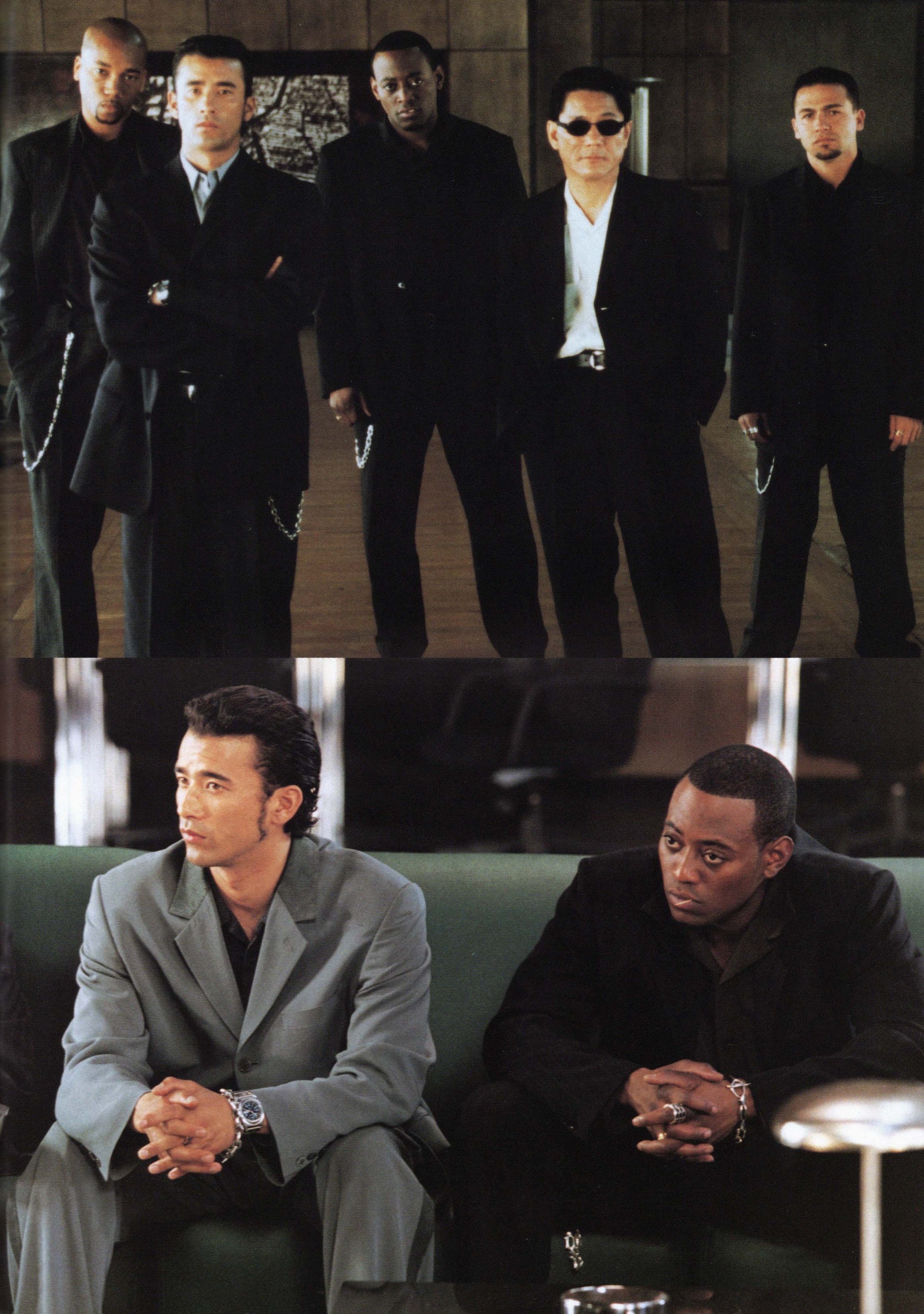

デニー

オマー・エプス

記者会見で来日した際に、会場の裏でせわしく衣装合わせをしたオマー。山本傘下に入る役者のなかでは、地味なデザインのものが主だが「黒人のスーツ姿は決まる」と山本耀司は太鼓判を押した。

後半からグレーのストライプのスーツに黒のシャツ。中盤では同じスーツにグリーンのシャツを合わせた(一番下)。

主に茶系のストライプのスーツを着用。新参者の手下としては、もっとも山本との絆を深める役柄なので、古参の舎弟である加藤の衣装と似たデザインになっている。特徴的な違いはストライブの幅と、「襟飾りの色。

こちらもグレーのスーツに黒のシャツを着用しているシーン。ここだけの打ち明け話だが、「デニーという役柄を通り越し、オマー・エプスとしてもたけしさんを敬愛していた」と真木蔵人。

やがては山本同様、開襟シャツを常用することに。衣装の変遷で登場人物の心の動きを表現するという演出が心憎い。

Denny

Omar Epps

When Omar came to Japan for the press conference, he hurriedly tried on outfits behind the venue. Though his outfits under Yamamoto’s group were mostly plain in design, Yohji Yamamoto gave his full approval: “Black men always look great in suits.”

In the latter half, he wears a gray pinstripe suit with a black shirt. In the middle portion, he pairs the same suit with a green shirt (bottom photo).

He mainly wears brown-toned striped suits. Since he plays a newcomer who develops the deepest bond with Yamamoto, his outfits are designed to resemble Kato’s, an older underling. The key differences are the width of the stripes and the color of the collar decoration.

Here too, he’s seen wearing a gray suit with a black shirt. A little behind-the-scenes anecdote: “Through playing Denny, Omar Epps came to admire Takeshi-san not just as a character, but personally,” said Claude Maki.

Eventually, like Yamamoto, he begins regularly wearing open-collar shirts. The evolving costumes cleverly reflect the characters’ emotional development.

加藤

寺島進

山本を追いかけて、わざわざ日本からロスへやってきたという忠誠心を強調するため、ほとんどのシーンで兄貴にならった開襟シャツを着ている。もっとも「どんなものを着ても山本の舎弟という色を出せる役者だから、比較的作りやすかった」と山本耀司。

成り上がってお洒落をするシーンは黒のシルクのシャツで。ペンダントは龍の頭を。モチーフにした。

ロスに到着したばかりの頃は、ダークブルーでストライプ模様が入ったスーツと、グレーのシャツで登場。まだ日本のヤクザっぽさが残っている。

中盤ではシャツが明るめの同系色に。「小柄ではあるけど、スタイルがいいので決まりやすい」と山本耀司写真では判別しにくいが、スーツにはストライプ模様が入っている。

ほとんどのシーンで愛用している茶系のスーツ。襟には同系色のラインをほどこした寺島の衣装はたけしとともに、最初に作ったものからほとんど変更が不要だった。

Kato

Susumu Terajima

To emphasize his loyalty—having followed Yamamoto all the way from Japan to Los Angeles—he wears an open-collar shirt in almost every scene, just like his boss. Yohji Yamamoto commented, “He was relatively easy to dress, since no matter what he wears, he gives off the vibe of Yamamoto’s underling.”

In scenes where he’s risen in rank and dresses more stylishly, he wears a black silk shirt. His pendant features a dragon’s head as its motif.

Upon first arriving in Los Angeles, he appears in a dark blue pinstripe suit with a gray shirt—still retaining that Japanese yakuza look.

In the middle of the story, his shirt is in a lighter tone of the same color family. “He may be small in stature, but he has a good build, so outfits look great on him,” said Yohji Yamamoto. It’s hard to tell from the photos, but the suit has pinstripes.

His most frequently worn suit is a brown-toned one. The collar has a line of a similar color added for detail. Alongside Takeshi’s, Terajima’s costume was among the first created and required almost no changes thereafter.

隠れたこだわり

ジャケットの裏地に凝ったり、シャツの襟の幅に凝ったり、とかく男は細部にこだわりたがる。実は「BROTHER」の面々も、目立たないところでずいぶんシャレこんでいる。男の粋とは、こういうものさ。

アクセサリー

つけたほうが絶対カッコいい、という山本耀司の提案から、アクセサリーも用意。ほとんどがシルバーなのはギラっと渋く光るところが魅力だから。銀は、強度が保てるギリギリの純度。「俺たちは成功したんだ」という気持ちを高めてほしい、と石も本物にこだわった。

財布と靴

映画中では財布が見えないので気づきようがないのだが、ケンが使っているご覧の財布は、靴とおそろいの蛇革。

アクセサリーのデザイン

ネックレス、ブレスレットの中央部、チェーンの留め金部分には蛇のデザインが。さすがにスクリーン上では見抜けません!

開襟シャツ

日本料理店で食事をするシーンでは、組員全員が山本のスタイルを真似て、開襟シャツを着ている。これはたけしのアイディア。この後のシーンから山本を慕うデニーも開ファッションに。

スクラップ・ファイル

山本耀司はほとんどデザイン画を書かない。人が着用して初めて自分のデザインが完成する、という表現哲学からなのか、頭の中にひらめいたものをいきなりパターンにおこす。衣装合わせの後はサイズや色の変更箇所をファイルに書きとめながら最終案を決定する。

チェーン

組織の一員である証しとして、山本の手下たちはチェーン付きの財布を使っている。社章や議員バッチをイメージして作った。

Hidden Details of Style

Men love to obsess over the details—whether it’s the lining of a jacket or the width of a shirt collar. The cast of Brother is no different; they show off their style in subtle, often unnoticed ways. True masculine elegance lies in these hidden touches.

Accessories

Accessories were added at Yohji Yamamoto’s suggestion: “They definitely look cooler with them.” Most of the pieces are silver, chosen for its refined, subdued shine. The silver used was of the highest purity that still maintained durability. Genuine stones were also used to heighten the feeling of “We made it.”

Wallets and Shoes

Though it isn’t visible in the film, Ken uses the wallet shown here—made of snakeskin to match his shoes.

Accessory Designs

The centerpieces of the necklaces and bracelets, and even the chain clasps, feature snake motifs. Naturally, these details are too small to spot on screen!

Open-Collar Shirts

In the scene where they eat at a Japanese restaurant, all the gang members mimic Yamamoto’s style and wear open-collar shirts. This was Takeshi’s idea. After that, even Denny, who admires Yamamoto, switches to the same fashion.

Scrap Files

Yohji Yamamoto rarely draws design sketches. Perhaps it stems from his philosophy that a design is only complete when worn by someone. Instead, he directly converts the ideas in his mind into patterns. After fittings, size and color adjustments are noted in a file to finalize the designs.

Chains

As a mark of being part of the organization, Yamamoto’s underlings all use wallets with chains—designed to evoke things like company badges or parliamentary pins.

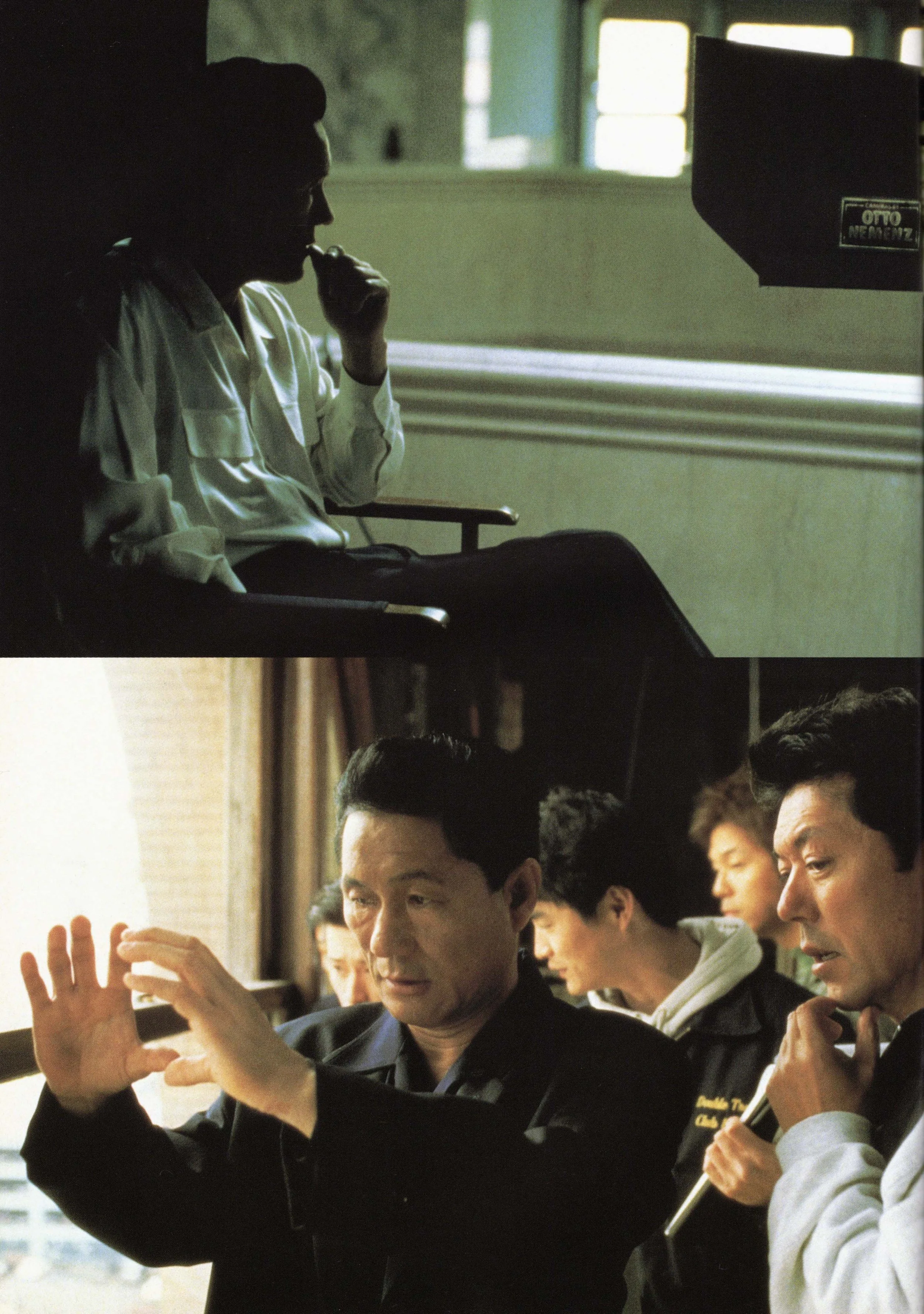

白瀬

加藤雅也

真木と同様、決まりすぎて衣装作りに苦労した。各役者とも衣装合わせではスーツ、シャツのセットを3パターンほど試着し、色、形、丈などを見ながら決定していくわけだが、白瀬は全部作り直しで3度の衣装合わせをした。

「想像していたより、細身だった」と山本耀司。上着は丈のほか、胸まわりを少しゆったりめにとって、さらに迫力を感じさせる工夫をした。ラメが入っているのも特徴。

美形なのでノーマルな型のスーツだと、単に〝おしゃれな人〞になってしまう。平気で人を殺す奴だという凶凶暴さを醸し出すために、上着丈を長めにした。ジャケットは3度目の衣装合わせでレザーに決定。

唯一、通常丈なのが喪服。全身姿は映画で見てください(笑)。シルクのネクタイに、チェーン付きのネクタイパーで飾りを。

物語の後半では、上の写真のラメ入りスーツに黒のシャツを。スーツも黒に見えるが、実際は濃紺と緑を混ぜた微妙な色合い。

Shirase

Masaya Kato

Like Maki, he looked too good in everything, making costume design a challenge. Each actor tried on three combinations of suits and shirts during fittings, adjusting color, shape, and length. Shirase required a complete overhaul and went through three fittings.

“His build was slimmer than I expected,” said Yohji Yamamoto. The jacket was made slightly roomier around the chest to give him a more imposing presence. It also features a subtle shimmer.

Because of his handsome features, a regular suit would’ve just made him look like a fashionable man. To suggest his cold-blooded violence—he’s someone who kills without hesitation—the jacket was made longer. In the third fitting, they settled on leather for the jacket.

The only standard-length suit he wears is his funeral outfit. You’ll have to see the full look in the movie (laughs). It’s paired with a silk tie and a tie pin with a chain for decoration.

In the second half of the story, he wears the glitter-accented suit with a black shirt, as seen in the above photo. The suit appears black, but is actually a subtle mix of deep navy and green.

石原

石橋凌

石原だけベストを着ているのは、単に「石橋さんはベストが似合うから」だとか。すでにロスで成功していたという役柄なので、白瀬とともに登場時はベージュ系でそろえ、山本傘下のダーク系と区別させた。

ネクタイを柄物にして 華やかさを添えた。ベストは下の写真のものとあわせて2種類用意され、いずれもレザー。

「山本組と区別させつつ、ジャパニーズはかっこいいんだぜ!ということを映画を見る人に伝えたかった」と、石原の衣装も3度目でようやく決定。白瀬同様、実はサスペンダーをしている。画面に写らなくても、役に入り込みやすい工夫をするのが耀同流。

葬儀のシーンではライト・ベージュのベスト。スーツの上着丈はやや長めになっている。役柄的に「俺はおしゃれをしたかったんだ!」という雰囲気を出したかったからとのこと。

蛇柄のプリント地のシャツに、ラメをほどこしたスーツ。山本耀司いわく、「派手でギラギラしたムードが欲しかったけど、趣味が悪すぎるのは嫌なので、原色を使わずにやばさを表現した」。

Ishihara

Ryo Ishibashi

Ishihara is the only one who wears a vest—simply because “Ishibashi-san looks good in one.” Since his character is already successful in L.A., he and Shirase initially appear in beige tones, to contrast with the dark-toned Yamamoto crew.

A patterned tie adds some flair. Two leather vests were prepared (see lower photo). Both are in leather.

“We wanted to distinguish him from Yamamoto’s group while also showing that Japanese guys can be stylish too,” said Yamamoto. Ishihara’s final look was also decided after three fittings. Like Shirase, he wears suspenders—even if they don’t show up on screen, they help him get into character.

In the funeral scene, he wears a light beige vest. His suit jacket is slightly longer than usual, meant to express a sense of “I wanted to be stylish” in his character.

He also wears a shirt with a snakeskin-style print, paired with a glitter-accented suit. Yohji Yamamoto said, “I wanted a flashy, flashy mood, but without going into bad taste—so I avoided using primary colors to express the danger.”

ジェイ

ロイヤル・ワトキンズ

長身でスマートなので、襟元を深めにしたデザインがよく似合う。スーツ、シャツとも全体的に暗さが目立つため、襟飾りを派手にした。

スーツはダークブルーで、ライトブルーのストライプが入っている。バスケットボールを持った写真のほうはグレーのストライプのパンツに、えんじのストライプのシャツ。

モー

ロンバルド・ボイヤー

黒人と比べるといまいち迫力に欠けるため、スーツやシャツの色にひと工夫加えて自己主張させた。「一般向けとして店頭に並べてもおかしくないくらいの渋さ」とは耀司評。

シャツはえんじで、細かいストライプ模様が入っている。スーツはモスグリーン。スウェードの靴は襟飾りと同系色に。ペンダントは鷲をモチーフにした。

光線の影響で本来の色と違って見えるが、スーツはチャコールグレーで、シャツはライトグレー。

アクセサリーにゴールドの指輪も身に付けている。

余談ですが、たけしはかつて出演した映画「JM」にちなんで、ジェイとエムという役名を考えていた。そんな名前はアメリカにない!と、モーに。

Jay

Royale Watkins

Tall and lean, Jay suits designs with a deep neckline. Because both his suits and shirts lean toward dark tones overall, a flashy collar decoration was added for contrast.

The suit is dark blue with light blue stripes. In the photo where he’s holding a basketball, he wears gray striped pants and a burgundy-striped shirt.

Mo

Lombardo Boyar

Compared to the Black characters, Mo lacks visual impact, so his suit and shirt colors were tweaked to help him stand out. Yamamoto remarked, “His style is subdued enough that it wouldn’t be out of place sold in regular stores.”

His shirt is burgundy with a fine stripe pattern. The suit is moss green. His suede shoes match the tone of his collar decoration. His pendant features an eagle motif.

Due to lighting, the colors may appear off in photos, but the suit is actually charcoal gray and the shirt is light gray.

He also wears a gold ring as part of his accessories.

As an aside, Takeshi originally wanted to name the characters Jay and M—as a nod to the movie Johnny Mnemonic (JM) in which he previously appeared. But “there’s no such name in America!”—so it became Mo instead.

BIOGRAPHY

2010

Yohji Yamamoto: My Dear Bomb

Published by Ludion

Written by Yohji Yamamoto and Ai Mitsuda

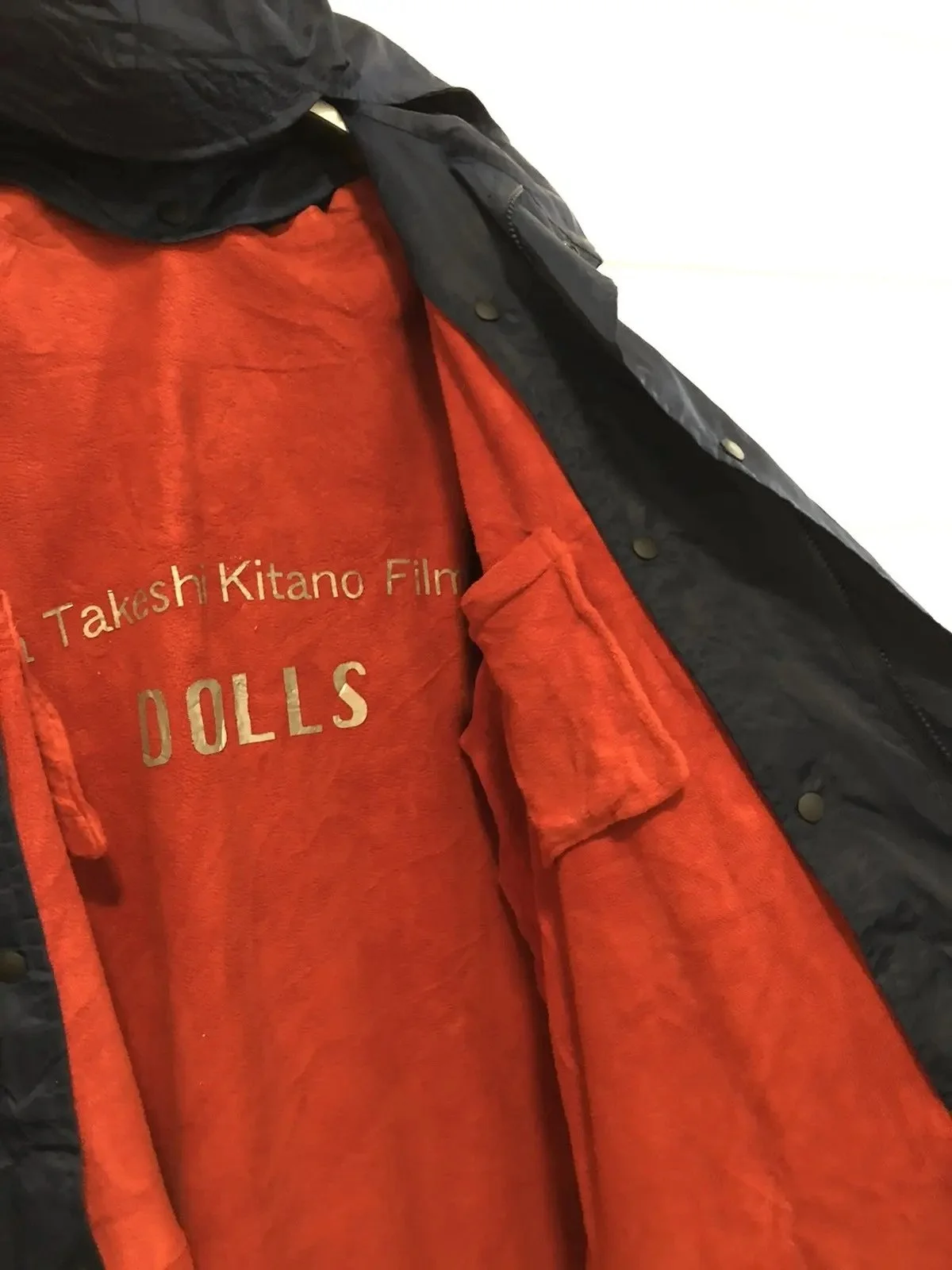

1999 Costume design for the film Brother, by director Takeshi Kitano

2002 Costume design for the film Dolls, by the director Takeshi Kitano

After Wim enjoyed such great success with Wings of Desire, he attracted various sponsors and decided to make the film Until the End of the World.

The project started to get more and more ambitious, expanding like a bubble. When it reached the point where it seemed they were going to have Wim film in hi-vision, I took him for advice from NHK, Japan's national broadcasting station.

We arrived, the two of us, but couldn't sit still.

Wim ended up grabbing a box of tissues that was in the room and began arranging it to look like a certain female body part. "No, no, that's not how it's shaped!" I said. For what seem like an eternity in that office at the national broadcasting station we played around with that box of tissues... at least that's how I remember it.

On the way home, just as we drove onto the ramp leading off the elevated highway, Wim blurted out, "Hey, Yohji, do you have something like this—some work you know won't be a success but that you just have to see through to the end?"

I was speechless for a second. Then, with my eyes still trained straight ahead, I answered, "I do have something like that."

Sometimes a project starts to inflate, like a bubble, and take on a life of its own.

Once Takeshi Kitano said, "In Hollywood movies they even spend a fortune on the costumes for the minor characters." He was probably jealous and wanted to use me to see what he might be able to do. I think Brother turned out better than Dolls in terms of the relationship between the costumes and the film.

Even though I've done it, I have some rather serious doubts about fashion designers doing the costumes for films. It is really very difficult to decide the limits on how far one should go with it. That's what makes costume design for films such challenging work.

The costumes for a film have to be subordinate to the vision as it appears in the script. They must never look to outshine the script. I've kept those ideas in mind with my costumes, and in the work I've done with Takeshi, Zatoichi (The Blind Swordsman) has actually been the most successful. For that project we had a specialist in film costumes join us, and after I came up with the concept I left the rest to her.

If they aren't handled carefully, the costumes for a film can overshadow the hero. So, in my case, it would probably be better to have me doing the film score instead.

The Japanese film director Yasujirō Ozu treats everyday sorts of topics from a disinterested perspective. Using his distinctive camera angles he doggedly pursues his subject, leaving the viewers heartbroken. He's not stuck in that claustrophobic worldview that comes from Japan's island mentality, treating always the clash between human emotions and the sense of duty. Ozu's themes have a universality that speaks to the whole world.

Takeshi Kitano, though, I think is closer to Akira Kurosawa. Kurosawa did grand epics, and he had some failures, too. He would just forge ahead, making the movies he had to before he could proceed to the next level.

The Takeshi films I like best are ones for which I didn't do the costuming, like Sonatine and Hana-Bi (Fireworks). In these especially he shows a unique sense of MA, the empty gaps in time and space. In the places where he wants a message to get across, he intentionally does not insert that message. I also like those points where his "dignity of violence" emerges.

Not so much as a creator of films, but as a friend, I worry a little about him these days.

山本耀司 AtoZ

Yohji Yamamoto AtoZ

March 2011

FASHION NEWS Special Vol.161

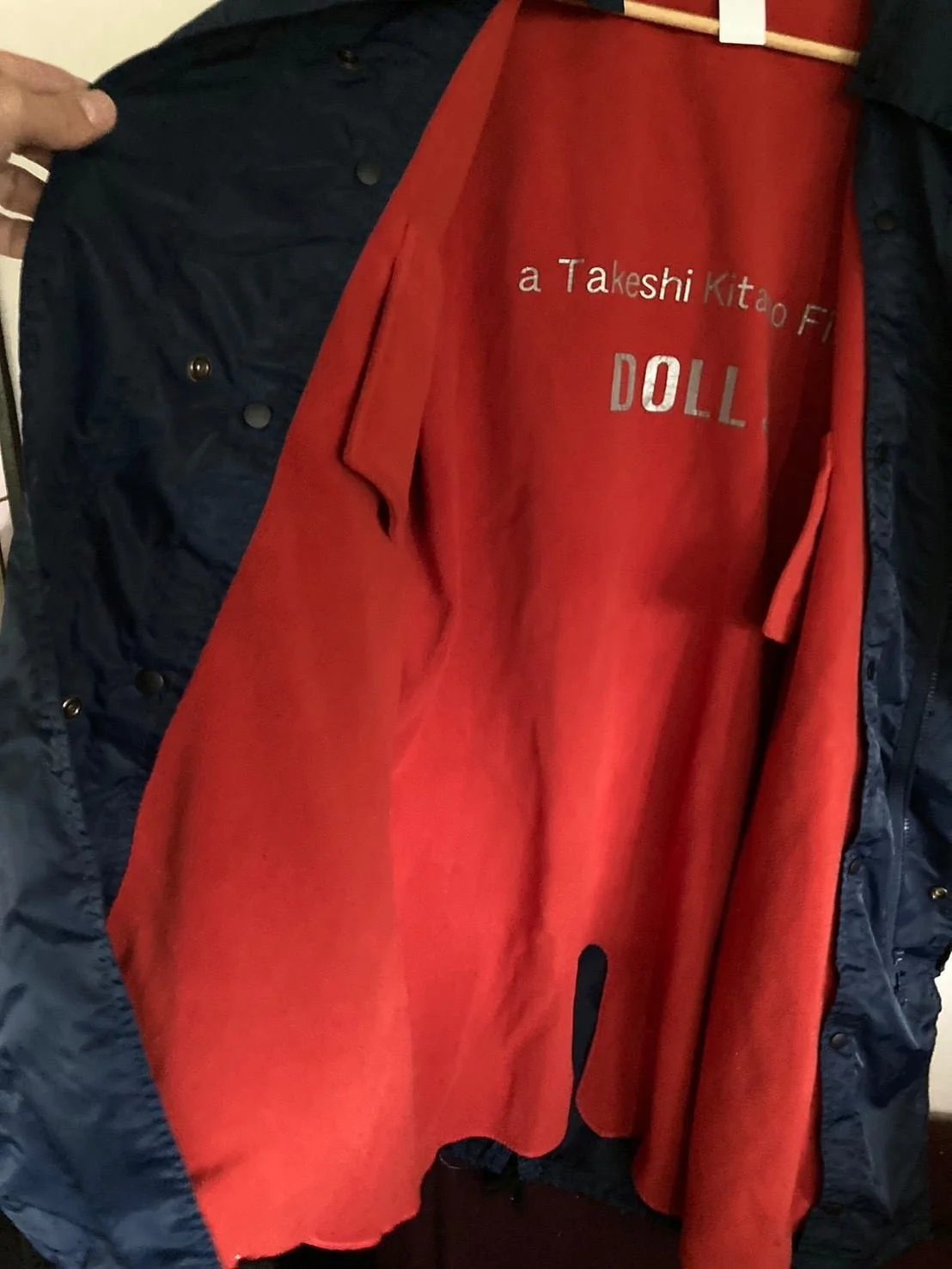

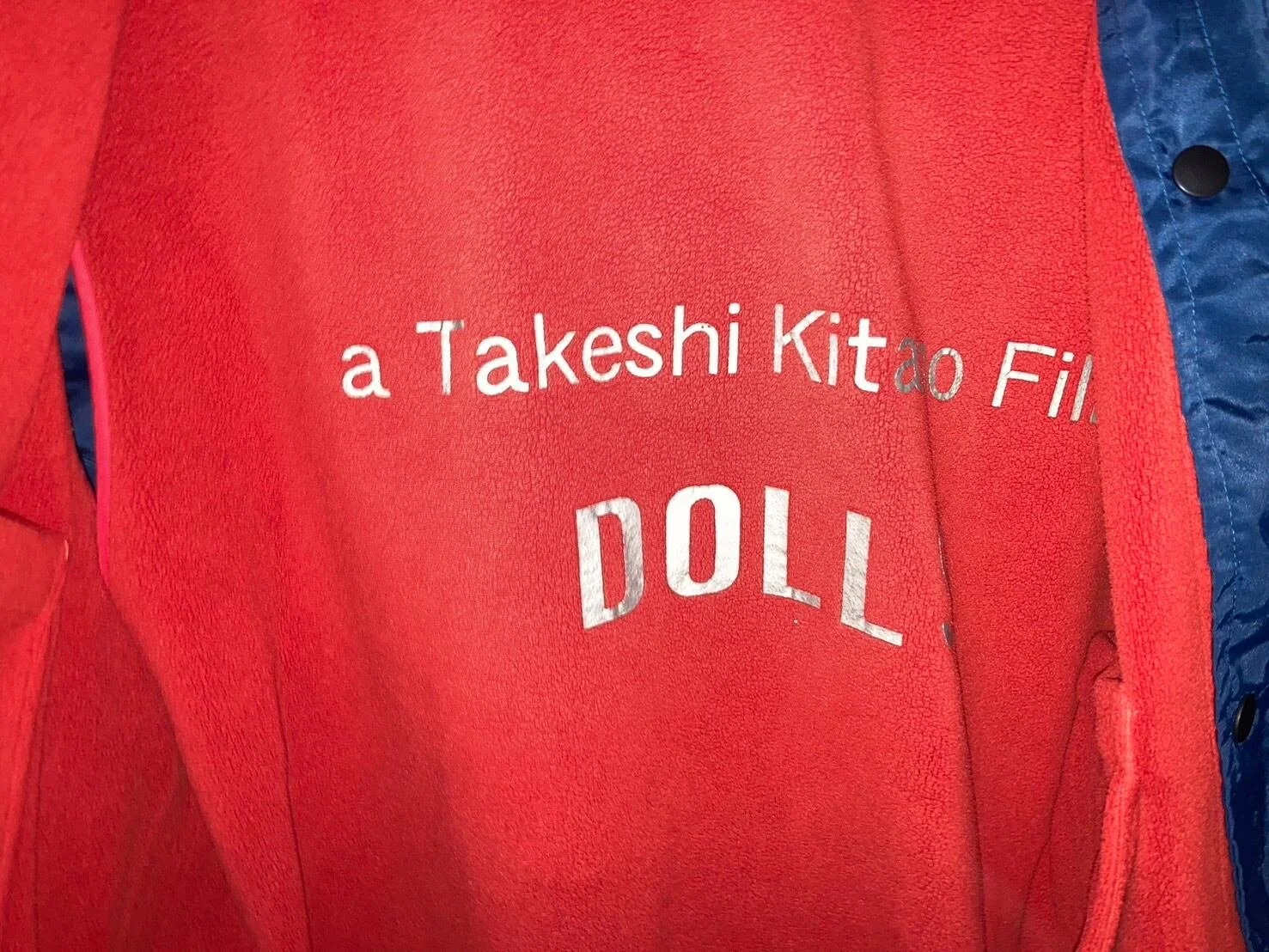

「Dolls[ドールズ]」監督:北野武 ©2002 バンダイビジュアル・TOKYO FM・テレビ東京/オフィス北野

「BROTHER」監督:北野武 ©2000 オフィス北野/レコーデッド・ピクチャー・カンパニー

「座頭市」監督:北野武 ©2003「座頭市」製作委員会

左から「Dolls[ドールズ]」、「BROTHER」、「座頭市」/すべてバンダイビジュアル

“Dolls” Director: Takeshi Kitano ©2002 Bandai Visual / TOKYO FM / TV Tokyo / Office Kitano

“BROTHER” Director: Takeshi Kitano ©2000 Office Kitano / Recorded Picture Company

“Zatoichi” Director: Takeshi Kitano ©2003 “Zatoichi” Production Committee

From left: “Dolls,” “BROTHER,” “Zatouichi” / All by Bandai Visual

Zatouichi

北野武との関係について

「BROTHER」「Dolls」「座頭市」「アウトレイジ」といった北野映画の衣装を手掛けている。制作工程は、北野武から依頼を受け、北野の発する断片的な言葉を頼りにイメージを広げる。耀司自身、台本は読まずに(アシスタントはもちろん読む)制作を進めるという。たとえば「BROTHER」では、「黒い背広でアメリカでドンパチ」という北野の言葉に対して「チェーンをぶら下げているでしょ?」と耀司。その後、それぞれの配役にドラゴンや鳥といった動物のイメージを重ね、緻密にデザインを進めた。北野は、耀司が手掛けた衣装に関しては、ほとんど一発OKを出すという。ちなみに武自身も「ヨウジヤマモト」の洋服を愛用していることは有名な話。

Zatouichi

Regarding the Relationship with Takeshi Kitano

Yohji Yamamoto has been in charge of costume design for Kitano's films such as BROTHER, Dolls, Zatoichi, and Outrage. The production process begins with a request from Kitano, and from there, Yamamoto expands on the imagery based on Kitano’s often fragmentary words. Interestingly, Yohji himself does not read the script (though his assistants of course do) as he proceeds with the design. For example, in BROTHER, Kitano simply said, “A black suit, with gunfights in America.” To that, Yamamoto responded, “So, you mean like hanging a chain?” From there, he associated each character with animal imagery such as dragons or birds, and carefully developed the designs. It’s said that Kitano usually gives an immediate “OK” to the costumes Yohji creates. Incidentally, it's also well known that Takeshi Kitano personally enjoys wearing Yohji Yamamoto clothing.

Designing Costumes: Takeshi Kitano

2014

Yamamoto & Yohji

Published by Rizzoli

“At that moment, something absolutely unexpected happened. A dramatic turn of events! My friend Yohji Yamamoto, the famous fashion designer, with whom I was so happy to work once again—he had been in charge of the costumes for Brother (2000)—had accepted to make the costumes for Dolls (2002). But the costumes designed by Yohji Yamamoto didn't correspond at all to the story.

When he showed up with his creations, I can assure you that it was nothing less than comical. What he had created was very beautiful, of course—sublime, even. But it wasn't what vagabonds wear! So I reminded him that these costumes had to be worn onscreen by a homeless man and woman. I supposed, and I understood, that Yamamoto had done it on purpose. The situation was special because I also knew that he was completely overworked. He was preparing fashion shows and the presentation of his latest collection in Paris at the same time. You can imagine his schedule. Knowing Yohji Yamamoto, he must have put in several sleepless nights to please me and complete this work. So I wasn't going to send him packing and ask him politely if he would mind starting all over again. But the fact remains that these flamboyant and brightly colored costumes caused a certain discomfort within the filming and production teams. What could we do? We were bewildered, completely stunned.

It was as I was thanking Yohji Yamamoto that I found the solution. We had to modify the screenplay, this time reinforcing the theatrical and figurative aspect of the story. So I decided to turn the story upside down to show manipulated human beings, exactly like in bunraku theatre. In fact, thanks to Yohji Yamamoto's costumes, I came back to my original idea, to the marionette theatre. It's a bit like he directed half the film all by himself! The costumes really influenced the production.”

— Takeshi Kitano (Excerpt from Kitano par Kitano with Michel Temman, Grasset Publications, 2010, pp. 161 & 162)

© 2002 BANDAI VISUAL, TOKYO FM, TV TOKYO, AND OFFICE KITANO

Dolls - Takeshi Kitano

June 16, 2013

The Insatiables on Tumblr

“I gave [Yohji Yamamoto] creative freedom in terms of costumes, almost as if he were making his own fashion show in the film. Strange as it may sound, I basically let Yohji decide without any indications or discussions. At the first costume fitting session, Yohji showed us the fall costumes for the bound beggars. Miho, the leading actress, was wearing a red dress, which looked as far as it could get from what beggars wear in real life! When I saw it, I almost fell down to the floor! Yohji asked me, ‘What do you think?’ And I thought to myself, ‘What the hell am I supposed to think? What are we going to do with this?’ I literally panicked momentarily. But after a while, I calmed down and decided, ‘Okay, their costumes do not have to be realistic, because it’s a human puppets’ story.’ With hindsight, that was a critical point in the course of the production of Dolls, because it was the moment I consolidated the concept of the film. So I just accepted the costumes as they were and the rest depended on how we, the crew, would use them.”

— Takeshi Kitano

'Fashion show' in a Takeshi Kitano movie: Yohji Yamamoto (24)

April 24, 2022

Nikkei Asia

Written by Yohji Yamamoto

Friendship between two men -- a spirit of generosity and chivalry.

At a karaoke shop in Roppongi, Tokyo --

One night, I was having drinks next to film director Takeshi Kitano. Around us, the members of the "Takeshi Army" were naked and flailing about wildly. But despite the chaos, Takeshi and I had a peaceful time together, as if we were in a separate world.

"Yohji-san. I've got enough material for eight movies."

"Eight? Tell me about one of them, then."

With a grin, he began to tell me an interesting anecdote.

Bound beggars.

It was a story of a male and a female beggars, which Takeshi himself had seen when he was working as an elevator boy in Asakusa. For some reason, the woman has a psychotic break, and for some reason, they are tied together by a cord.

What happened in their past? What fate awaits them? The fantasy grew wilder and wilder.

"What a sad and yet beautiful story," I said. "I'd love to do the costumes for it."

That promise made over drinks ended up becoming reality.

I am a big fan of Kitano films. My favorites include "Sonatine," "Kids Return" and "HANA-BI," among others. I had just taken charge of the costumes for "BROTHER" (released in 2001), and I was ready to accept any request from Takeshi, who I greatly respect, no matter what it was.

I was planning the costumes, when I started to find out that bunraku, a traditional Japanese puppet theater, would be involved in the plot. "This is bad," I thought. I am a clothing tailor. So I went to Osaka to see bunraku performances and did my own research. I may have gone a bit overboard in my enthusiasm.

"I want to capture the four seasons of Japan."

When Takeshi said this in our meeting, I made a declaration of my own.

"I want to hold a fashion show in the movie."

I met with Miho Kanno, the lead actress, and developed my own image of the film. The first scene would be "autumn." I wanted to create a slightly undisciplined atmosphere, so I tailored a loose knit in bright red.

When Takeshi saw the costume for the first time, he was terribly confused. It was a homeless person's costume, so he imagined something more like a worn-out jersey. But the scene was "autumn." There was bright red foliage in the background.

My biggest worry was whether the colors would clash with the background. But when I checked the image, I found that the red shined through unexpectedly brightly.

"This is good. OK, we'll shoot a fashion show in the film."

Takeshi completely changed his mood, and he was on board, too.

I tailored the costumes for all of the characters except the extras. However, the hardest part was the padded kimono worn by Kanno and her counterpart, Hidetoshi Nishijima. In the script, there was only one line, which read, "There are gaudy padded kimono hung to dry in front of the farmhouse." I guess the intention was to synchronize it with the dolls used in the bunraku.

(Damn it...)

It is easy enough to write a sentence, but no one can imagine how much work it would be for the people who make the costumes.

Two padded kimono, one for a woman and one for a man, were made using Yuzen dyeing by Chiso, an old Kyoto Yuzen company formed in the 16th century. They cost more than 10 million yen. I paid for everything myself. But my relationship with Takeshi is not about money, but a friendship between two men. It is a spirit of generosity and chivalry.

And thus, "Dolls" was released in 2002. Although it did not set a box-office record, it is apparently being used in art schools around the world as a teaching tool for the use of color. It holds important memories for me as well.